Winter Solstice

The Winter Solstice is an astronomical event that occurs annually around December 21st in the Northern Hemisphere (around June 21st in the Southern Hemisphere). It marks the shortest day and longest night of the year in the Northern Hemisphere, while in the Southern Hemisphere, it is the longest day and shortest night.

During the Winter Solstice, the Sun reaches its lowest point in the sky, resulting in the shortest duration of daylight and the longest night of the year in the Northern Hemisphere. Following the Winter Solstice, the days gradually start to lengthen as the Sun appears to move higher in the sky. This marks the symbolic "rebirth" of the Sun. From an astronomical perspective, the Winter Solstice is caused by the tilt of Earth's axis and its orbit around the Sun. It marks a crucial point in the solar calendar and plays a role in various cultural and agricultural practices.

The Winter Solstice holds cultural and spiritual significance in many traditions and religions around the world. It's often associated with themes of rebirth, renewal, and the triumph of light over darkness. For example, various cultures celebrate holidays like Yule, Christmas, Dongzhi (in East Asia), and Inti Raymi (in the Andes). Some ancient cultures constructed monuments or alignments that were specifically designed to capture the sunrise or sunset on the Winter Solstice. Notable examples include Stonehenge in England and Newgrange in Ireland.

Today, the Winter Solstice is celebrated knowingly or unknowingly in various ways, ranging from traditional religious ceremonies to secular gatherings focused on nature and community. Some people use it as a time for reflection, setting intentions, and spending time in nature.

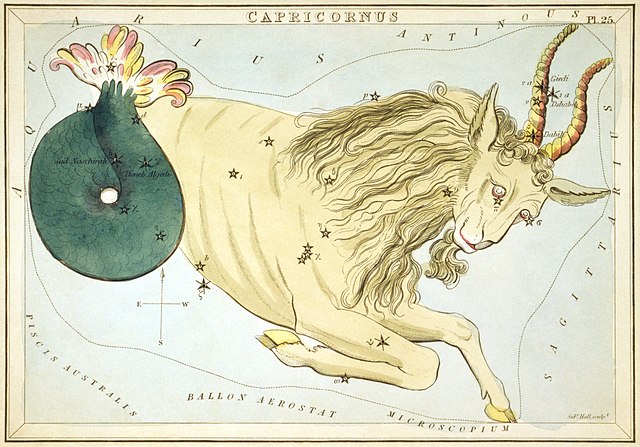

Astrological perspective

The Winter Solstice heralds the entry of the Sun into the zodiac sign of Capricorn. Capricorn is an earth sign associated with ambition, discipline, and practicality. This transition brings a focus on long-term goals, career aspirations, and the pursuit of stability. Capricorn's earth element emphasizes practicality and a connection to the physical world. The Winter Solstice encourages us to ground ourselves, work diligently towards our goals, and seek wisdom from our experiences. Capricorn is a Cardinal sign, which means it is associated with initiating energy, leadership, and taking charge. Capricorn is ruled by Saturn, the planet of discipline and responsibility. During the Winter Solstice, there may be an increased awareness of the need for structure, organization, and a methodical approach to achieving one's ambitions. The Winter Solstice marks the beginning of the winter season, and it's a time when many people feel motivated to set practical goals and work towards them.

The Winter Solstice is a natural point for reflection, as it marks the end of the solar year. It's a time to assess accomplishments, acknowledge challenges, and set intentions for the year ahead. The Winter Solstice also carries spiritual significance as it symbolizes the rebirth of the Sun. After this point, the days gradually lengthen, signifying the return of light and the promise of new beginnings. The Winter Solstice is a time when many cultures celebrate ancient traditions and customs. It often includes rituals that honor ancestors, acknowledge the cycle of life and death, and embrace the wisdom passed down through generations.

The Winter Solstice represents a balance between the longest night and the return of the Sun. It invites introspection, inner work, and finding meaning in the quieter, darker aspects of life. It's a time for inner work, establishing foundations, and preparing for the return of light and growth in the months ahead.

Various celebrations and traditions associated with the Winter Solstice

Here is a list of various celebrations and traditions associated with the Winter Solstice from cultures around the world:

-

Christmas (Christian Community)

Dongzhi celebrates the arrival of winter. Families gather to eat special foods like tangyuan (sweet rice dumplings) and participate in various customs and activities.

-

Dongzhi Festival (China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam and other East Asian countries)

Dongzhi celebrates the arrival of winter. Families gather to eat special foods like tangyuan (sweet rice dumplings) and participate in various customs and activities.

-

Inti Raymi (Peru and parts of Bolivia and Ecuador, Andes Region, South America)

Inti Raymi, or the "Festival of the Sun," was an ancient Incan celebration of the winter solstice and the sun god, Inti. It involved religious ceremonies, music, dance, and feasting.

-

Pancha Ganapati (Hindu communities worldwide, especially in Western countries)

Pancha Ganapati is a modern Hindu festival created in the 1980s. It celebrates Lord Ganesha and involves family gatherings, feasting, gift-giving, and artistic expressions of love and harmony.

-

Sanghamitta Day (Sri Lanka and other Buddhist communities)

Sanghamitta Day celebrates the arrival of Sanghamitta, the daughter of Emperor Ashoka, in Sri Lanka, bringing with her a sapling of the Bodhi Tree under which the Buddha attained enlightenment.

-

Saturnalia (Ancient Rome)

Saturnalia was a week-long Roman festival honoring the god Saturn. It included feasting, gift-giving, role-reversal between masters and slaves, and general merrymaking.

-

Shab-e Yalda (Iran)

Shab-e Yalda, meaning "Night of Birth," is an Iranian festival celebrating the arrival of winter and the longest night. Families gather, light candles, recite poetry, and eat fruits, nuts, and special foods.

-

Soyal (Hopi and Zuni Tribe, Native American, Southwest United States)

Soyal is a Hopi winter solstice ceremony focused on bringing the sun back after the shortest day of the year. It involves dances, rituals, and prayers for the return of the sun's warmth and light.

-

Korochun and Koliada (Slavic regions)

Korochun is a traditional Slavic winter solstice celebration that predates the Christianization of Eastern Europe. Koliada, also known as koleda stands as the traditional Slavic term encompassing the period spanning from Christmas to Epiphany.

-

Lohri (Punjab region in India and Pakistan)

Lohri marks the end of winter and is celebrated with bonfires, music, dancing, and the sharing of traditional foods.

-

Yule (Scandinavia, Germany, UK and other parts of Northern Europe)

Yule celebrates the return of the sun and the promise of longer days. It involves lighting fires, decorating evergreen trees, feasting, and exchanging gifts.

-

Ziemassvētki (Latvia)

Ziemassvētki is a Latvian celebration that combines elements of Christmas and ancient pagan traditions. It involves rituals, songs, and the decoration of a special "Yule Log".

Christmas

(Christian Community)

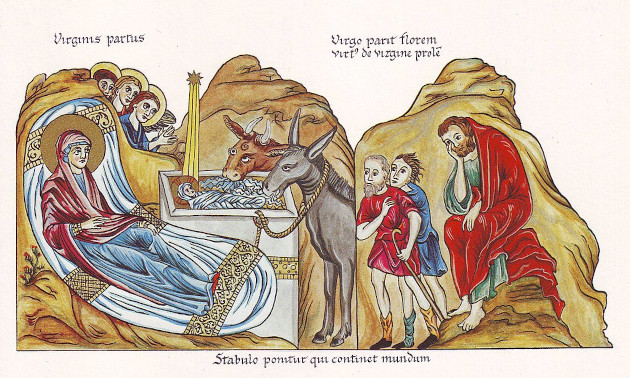

Christmas is a Christian holiday celebrated annually on December 25th to honor the birth of Jesus Christ. It's considered one of the most significant celebrations in Christianity. The holiday has both religious and cultural aspects, and its origins date back to the early Christian traditions and ancient pagan celebrations.

Nativity of Christ, medieval illustration from the Hortus deliciarum of Herrad of Landsberg (12th century) (source: Wikipedia)

The exact date of Jesus' birth is not mentioned in the Bible, and December 25th was chosen by early Christians to coincide with existing pagan festivals like Saturnalia (Roman) and Yule (Germanic), which were celebrated around the winter solstice. By aligning Christmas with these existing festivals, it helped ease the transition for people converting to Christianity.

The holiday and its December date started way back in ancient times, maybe around the 2nd century. They've got a few possible beginnings for why December 25th was picked. This historian named Sextus Julius Africanus thought Jesus was conceived on March 25th (which he also believed was the day the world was made). If you count nine months from that, it points to a December 25 birthday for Jesus.

In the 3rd century, when the Roman Empire hadn't accepted Christianity yet, they had this big celebration on December 25th for the rebirth of the Unconquered Sun (called Sol Invictus). This day marked longer days after winter and came after the fun Saturnalia festival when folks partied and gave gifts. It also happened to be the birthday of a god called Mithra, who was really popular with Roman soldiers and was all about light and loyalty.

The church in Rome made December 25th the official Christmas celebration in the year 336, back when Emperor Constantine was in charge. This move was a way to bring Christian celebrations in line with other big parties happening around that time, making it easier for everyone to get on board with Christianity.

Christmas traditions have evolved over centuries, blending Christian customs with cultural practices from various regions around the world.

Dongzhi Festival

(China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam and other East Asian countries)

The Dongzhi Festival, also known as the Winter Solstice Festival (Chinese: 冬至; pinyin: Dōngzhì; translating to 'winter's extreme'), is a revered traditional Chinese celebration observed during the Dongzhi solar term, aligning with the winter solstice, usually falling between December 21st and 23rd.

The origins of Dongzhi can be traced back to ancient Chinese beliefs in the harmony between nature, yin and yang principles, and the cyclical rhythm of the universe. Rooted in the yin and yang philosophy, this festival reflects the ideals of cosmic balance and harmony. It marks a pivotal moment when, following the festivities, days begin to lengthen, ushering in increased daylight hours and the upsurge of positive energy. This cyclical transition is deeply symbolic, encapsulated by the I Ching hexagram fu (Chinese: 復, "Returning"), signifying philosophical resurgence and renewal.

The Dongzhi Festival traces back to the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD). Legend holds that a sage named Zhou Feng first identified the winter solstice in China using a sundial. Since then, Winter Solstice, known as Dongzhi, has held significant cultural importance. There's an age-old belief that Dongzhi surpasses the importance of Chinese New Year. In the eras of the Tang Dynasty (618–907) and Song Dynasty (960–1279), government officials were granted a generous 7-day break. This holiday allowed them to reunite with their families, marking the occasion by honoring both heaven and their ancestors.

Dongzhi is a time for families to come together, share a meal, and strengthen family bonds. Tangyuan, glutinous rice balls often served in a sweet soup, are a traditional Dongzhi delicacy symbolizing reunion and unity. Some families use Dongzhi as an occasion to pay respects to their ancestors, offering prayers and making offerings at ancestral shrines or gravesites.

The festival's observance varies across different regions of China and among Chinese communities worldwide, with diverse local customs and traditions associated with Dongzhi. In certain regions, customs like eating dumplings, steamed cakes, or other specific regional dishes are part of the festival. Other traditions might involve making offerings to deities or performing rituals to welcome the new season.

While Dongzhi is deeply rooted in ancient Chinese culture and its connection to the winter solstice, it continues to be celebrated today as a time for family gatherings, reflection, and embracing the changes in the natural world.

Inti Raymi

(Peru and parts of Bolivia and Ecuador, Andes Region, South America)

The Inti Raymi, derived from Quechua meaning "Inti festival," stood as a cherished religious rite within the Inca Empire, venerating the deity Inti, the revered sun god in Incan belief. This celebration marked the winter solstice, signifying the shortest day of the year between sunrise and sunset, and it heralded the Inca New Year, signifying the lengthening of daylight hours. In regions south of the equator, such as during the Gregorian months of June and July, these months are considered winter. This significant ceremony was observed on June 24th.

"Inti" refers to the sun, while "Raymi" translates to "celebration" or "festival" in Quechua, the language of the Incas. The festival venerates Inti for providing warmth, light, and sustenance to life on Earth.

During the height of the Inca Empire, the Inti Raymi held a preeminent position among four essential ceremonies celebrated in Cusco, as chronicled by Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. The festivities unfolded at the Haukaypata, the central plaza within the city. The Inca civilization, deeply connected to nature, believed in the divinity of the sun and its pivotal role in their agricultural cycles and prosperity. The festival was accompanied by vibrant festivities, music, dance, and communal feasting. People came together to celebrate the sun's return and the renewal of life. The festival involved ceremonial rites led by the Inca king and priests to honor Inti. Offerings and sacrifices were made to ensure the sun's continued blessings upon the land.

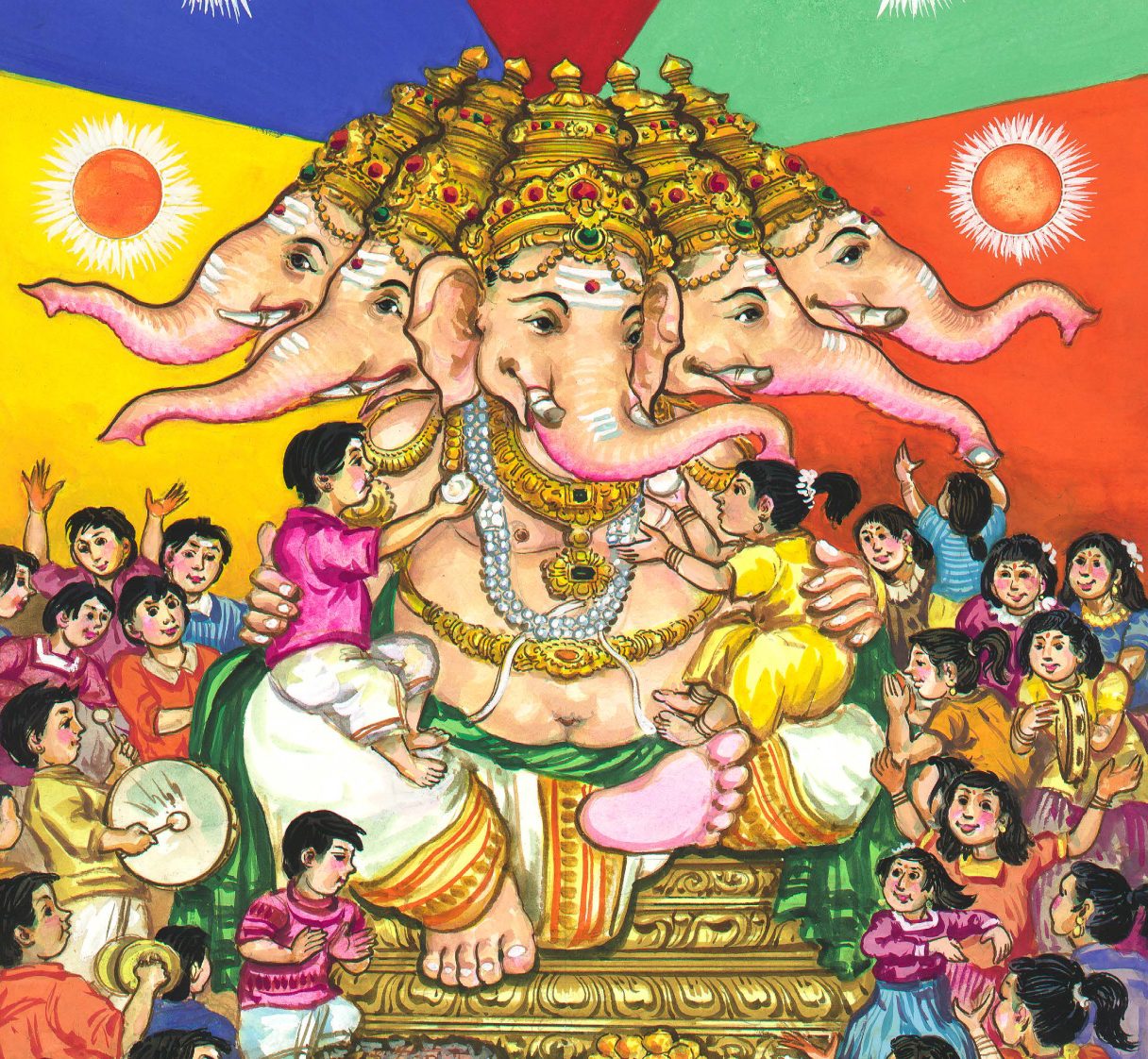

Pancha Ganapati

(Hindu communities worldwide, especially in Western countries)

Pancha Ganapati is a modern Hindu festival celebrated from December 21st to 25th, created by Sivaya Subramuniyaswami in the late 20th century. It is dedicated to the Hindu deity Ganesha, the elephant-headed god of wisdom, prosperity, and new beginnings. Pancha Ganapati is not rooted in ancient tradition but is a contemporary celebration embraced by many Hindu households. Its connection to astrology lies in its timing and the symbolic association with the five elements.

Pancha Ganapati was introduced in the 1980s by Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, an American-born Hindu guru. It was created as a way to provide a Hindu alternative to Western Christmas celebrations. Pancha Ganapati is celebrated from December 21st to 25th, which coincides with the Winter Solstice in the Northern Hemisphere. The Winter Solstice marks the shortest day and longest night of the year, symbolizing the return of light and the promise of longer days. Pancha Ganapati is a five-day festival, with each day dedicated to a different aspect of Lord Ganesha. It emphasizes fostering love, unity, and spiritual growth within the family.

Each day focuses on a specific aspect of Ganesha, highlighting his multifaceted nature and the various qualities he embodies:

-

First Day (Green)

On the first day, a green cloth is placed on a shrine, and Ganesha is worshipped as the Lord of Love and Harmony.

-

Second Day (Blue)

The second day focuses on Ganesha as the Giver of Boons and is represented with a blue cloth. Family members exchange gifts and seek blessings for the fulfillment of their desires.

-

Third Day (Red)

On the third day, Ganesha is honored as the Remover of Obstacles. A red cloth is used to represent his power to remove difficulties and challenges.

-

Fourth Day (Yellow)

This day is dedicated to Ganesha as the Bestower of Learning and Wisdom. Yellow represents the blossoming of intelligence and knowledge.

-

Fifth Day (Multi-Colored)

The final day celebrates Ganesha in all his glory. A multicolored cloth is used to symbolize the full spectrum of Ganesha's attributes.

Pancha Ganapati is celebrated by Hindu families, particularly in regions where there is a cultural fusion of Eastern and Western traditions. It has gained popularity as a way to embrace the spirit of giving, love, and unity during the holiday season.

In summary, Pancha Ganapati is a modern Hindu festival dedicated to Lord Ganesha, celebrated over five days from December 21st to 25th. Its connection to astrology lies in its timing during the Winter Solstice and its emphasis on unity, love, and spiritual growth within the family. The festival serves as a meaningful way for Hindu households to celebrate the holiday season with a focus on the qualities embodied by Lord Ganesha.

Sanghamitta Day

(Sri Lanka and other Buddhist communities)

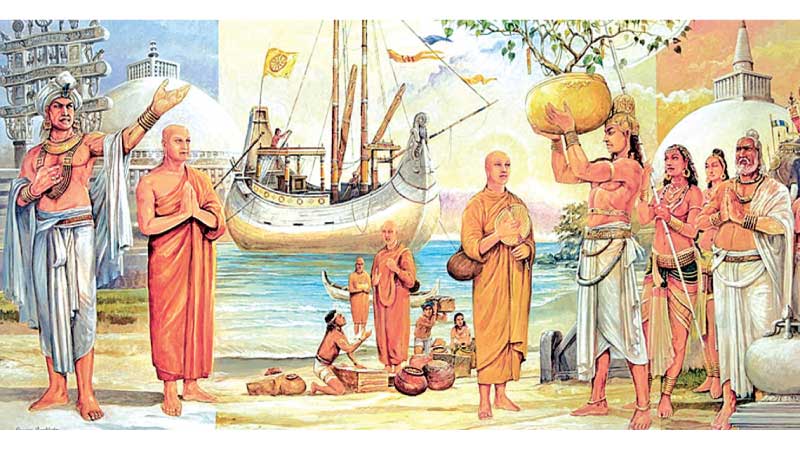

Saṅghamittā, also known as Saṅghamitrā in Sanskrit and referred to as Ayapali in her nun's name, lived from 282 BC to 203 BC. She was an esteemed Indian Buddhist nun, believed to be Emperor Ashoka's eldest daughter according to Sri Lankan tradition. Alongside her brother Mahinda, she embraced the Buddhist monastic order.

At the request of King Devanampiya Tissa, contemporaneous with Ashoka, Saṅghamittā and Mahinda journeyed to Sri Lanka to propagate Buddha's teachings. Initially hesitant, Ashoka eventually consented to her overseas mission due to Saṅghamittā's persistent insistence. Accompanied by other nuns, she ventured to Sri Lanka to establish the Bhikkhunis, fully ordained female Buddhist monastics, fulfilling King Tissa's wish to ordain Queen Anulā and other court women in Anuradhapura who sought to embrace nunhood following Mahinda's conversion of them to Buddhism.

The daughter of Emperor Dharmasoka, Sangamitta theri, bringing with her a sapling of Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi (source: dailynews.lk)

Saṅghamittā's monumental contributions to Buddhism in Sri Lanka were pivotal. She established the Bhikkhunī Sangha or Meheini Sasna (Order of Nuns), a foundational step that led to the establishment of the Buddhist Female Monastic Order in Theravāda Buddhism. Her influence extended beyond Sri Lanka, impacting Burma, China, and Thailand, notably shaping the Buddhist monastic order.

Celebrated annually on the Full Moon day of December, Uduvapa Poya or Uposatha Poya, and honored as Sanghamittā Day by Theravāda Buddhists in Sri Lanka, the occasion commemorates the planting of the revered Bodhi tree brought by Saṅghamittā herself to Anuradhapura. This tree, a cherished symbol of Buddhism, still thrives as a testament to her enduring legacy.

Saturnalia

(Ancient Rome)

Saturnalia was an ancient Roman festival dedicated to Saturn, the god of agriculture, wealth, and renewal. It was one of the most significant and oldest festivals in Rome, celebrated annually on 17 December of the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities through to 25 December.

Saturn wearing his toga “capite velato” and holding a sickle (fresco from the House of the Dioscuri at Pompeii, Naples Archaeological Museum) (source: Wikipedia)

The origins of Saturnalia can be traced back to agricultural and rural practices in ancient Rome. Initially, it was a festival to honor Saturn for the bountiful harvest, celebrated during the winter solstice, symbolizing the return of light and the sun's rebirth. In Roman mythology, Saturn was an agricultural deity who was said to have reigned over the world in the Golden Age, when humans enjoyed the spontaneous bounty of the earth without labour in a state of innocence. The revelries of Saturnalia were supposed to reflect the conditions of the lost mythical age. The festival likely originated in the 5th century BCE or earlier, gaining prominence as an official Roman holiday during the Republic. Saturnalia's observance became more elaborate and extended under the influence of different rulers and evolving Roman traditions.

"The first inhabitants of Italy were the Aborigines, whose king, Saturnus, is said to have been a man of such extraordinary justice, that no one was a slave in his reign, or had any private property, but all things were common to all, and undivided, as one estate for the use of every one; in memory of which way of life, it has been ordered that at the Saturnalia slaves should everywhere sit down with their masters at the entertainments, the rank of all being made equal."

Saturnalia held multiple meanings and customs. It was a time of joyous celebration marked by feasting, drinking, and revelry. People enjoyed lavish banquets, indulged in rich foods, and partook in entertainment. An integral part of Saturnalia was the temporary reversal of social roles. Slaves were given temporary freedom and treated as equals by their masters. This reversal allowed for a sense of social equality and camaraderie. Exchanging gifts, especially small tokens like figurines, candles, or sweets, was customary during Saturnalia. These gifts symbolized goodwill, friendship, and prosperity. Houses were adorned with greenery, such as evergreen boughs and wreaths, symbolizing life and renewal. Gambling, games, and public festivities were also common during this time.

Saturnalia (1783) by Antoine-François Callet, showing his interpretation of what the Saturnalia might have looked like (source: Wikipedia)

The festival typically lasted for several days, during which normal social conventions were relaxed, and people engaged in festivities and joviality. Saturnalia's influence extended beyond its original agricultural significance, becoming a significant cultural event that persisted for centuries in Roman society. As Christianity became the dominant religion in Rome, some Saturnalia customs and traditions were adapted or absorbed into Christmas celebrations, influencing elements like gift-giving and the festive spirit associated with the holiday season.

Shab-e Yalda

(Iran and Greater Iran)

Yalda Night, known as Shab-e Yalda in Persian (شب یلدا) or Chelle Night (شب چلّه), is an ancient festival observed in Iran, Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Iraqi Kurdistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Dagestan, and Turkey, coinciding with the winter solstice. It typically falls on December 20th or 21st in the Gregorian calendar and spans the night between the last day of the ninth month (Azar) and the first day of the tenth month (Dey) in the Iranian solar calendar.

This festivity is widely celebrated across Iran and Greater Iran, encompassing regions like Azerbaijan, Iraqi Kurdistan, Balochi areas, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. It holds great cultural significance in Persian culture and has roots in Zoroastrian traditions. The festival has its origins in ancient Persian beliefs and Zoroastrian traditions, where the winter solstice was considered a time of significance, symbolizing the triumph of the sun god, Mithra, over darkness and the resurgence of light.

During this longest and darkest night of the year, families and friends come together to share meals, indulge in conversations, and engage in the reading of poetry, notably the works of Hafez and Shahnameh, often continuing well past midnight. Fruits, nuts, and especially pomegranates and watermelons, hold special significance, with their red hues symbolizing the vibrant dawn and the essence of life.

The revered poetry from Divan-e Hafez, commonly found in Iranian households, is recited or read during various occasions, including Shab-e Yalda and Nowruz. Recognizing its cultural importance, Shab-e Yalda was officially listed as a National Treasure in Iran in 2008, affirming its place in the country's heritage and traditions.

Today, Shab-e Yalda continues to be celebrated by Persians and Iranians worldwide as a cherished cultural observance, symbolizing unity, hope, and the promise of renewal as the darkness of the longest night yields to the gradual return of light.

Soyal

(Hopi and Zuni Tribe, Native American, Southwest United States)

Soyal is a significant traditional ceremony observed by the Hopi and Zuni Native American tribes, marking the winter solstice and heralding the arrival of a new year. It holds immense cultural and spiritual importance, signifying renewal, harmony, and the continuation of life. Participants ceremonially bring the sun back from its long slumber, mark the beginning of another cycle of the Wheel of the Year, and work on purification. Pahos prayer sticks are made prior to the Soyal ceremony, to bless all the community, including homes, animals, and plants. The sacred underground kiva chambers are ritually opened to mark the beginning of the Kachina season.

Soyal, also known as Soyalangwul, is a ceremonial event that signifies the turning point of the year, celebrating the winter solstice, which typically occurs around December 21st. It marks the beginning of a new cycle, both in nature and in the lives of the Hopi and Zuni people, focusing on rejuvenation and the balance between light and darkness. The ceremony has ancient roots deeply embedded in Hopi and Zuni cosmology and traditions. It's believed to have been practiced for centuries, passed down through oral traditions and rituals. Soyal aligns with the cycles of nature, emphasizing the rebirth of the sun and the return of longer days following the shortest day of the year.

Soyal involves prayers, songs, dances, and ceremonial rituals led by spiritual leaders or kachinas (spiritual beings). These rituals are performed to honor the sun, seek blessings for the community, and ensure harmony and balance in the coming year. It's a time for purification and renewal, both for individuals and the community. The ceremonies aim to cleanse the past and welcome a fresh start. Kachinas play a significant role in Soyal. They are revered as messengers between the spiritual and human worlds, participating in the rituals and conveying blessings for the future. Soyal brings together the community in a spirit of unity, with families and tribes joining in shared activities, feasting, and storytelling.

Soyal is a deeply spiritual and communal observance, emphasizing the interconnectedness of humans with nature and the importance of maintaining balance and harmony. It reflects the cultural heritage and wisdom of the Hopi and Zuni tribes, nurturing a sense of renewal and optimism for the year ahead.

Korochun and Koliada

(Slavic regions)

Korochun is an ancient celebration from Slavic traditions, happening on December 21st, marking the winter solstice. It's all about the Sun's rebirth, and it goes way back before Christianity came to Eastern Europe. This special day has a lot of meaning in Slavic stories and in how nature changes.

Celebrations on December 21 on the longest night of "Koročun" or "Kračun" (source: avatars.dzeninfra.ru)

It's believed that during Korochun, the Black God and other dark spirits were at their strongest. People would celebrate on December 21st, the longest night of the year, and believed that the old sun, called Hors, got smaller as the days got shorter. On December 22nd, which was the winter solstice, it was thought that Hors died because of the Black God's dark powers. But on December 23rd, Hors came back to life as the new sun, known as Koleda.

Some experts think that during this celebration, Slavic folks honored their ancestors. They lit fires at graveyards to keep their loved ones warm, had big meals to remember and feed the spirits of the dead, and even lit wooden logs at crossroads. Over time, in some Slavic languages, the word "Korochun" came to mean the unexpected passing of a young person and the bad spirit thought to cause it.

Koliada, also known as koleda (Cyrillic: коляда, коледа, колада, коледе), stands as the traditional Slavic term encompassing the period spanning from Christmas to Epiphany. This term encapsulates a range of Slavic Christmas-related customs, with origins dating back to pre-Christian eras. It signifies a festive period celebrated towards the end of December, specifically honoring the sun's significance during the winter solstice in the Northern Hemisphere. Koliada involves groups of singers who travel from house to house, serenading residents with carols and spreading joyous melodies during this season of celebration.

Lohri

(Punjab region in India and Pakistan)

Lohri stands as a widely embraced winter festival in Northern India, particularly cherished in the Punjabi folk traditions. Rooted in the legends and significance attributed to the Punjab region, Lohri holds multiple narratives that connect it to this vibrant cultural tapestry.

Students wearing traditional Punjabi outfits perform a ritual around a bonfire to celebrate Lohri (source: Getty Images)

Many perceive Lohri as a marker of the winter solstice's passage, symbolizing the conclusion of winter. It signifies a joyous welcome to longer days and the sun's journey into the Northern Hemisphere, celebrated fervently by the people in the northern reaches of the Indian subcontinent. This festive occasion aligns with the solar segment of the lunisolar Punjabi calendar, customarily observed on the eve of Maghi and consistently falling on January 13th.

Lohri carries official recognition as a holiday in Punjab, Jammu, and Himachal Pradesh, fostering a vibrant atmosphere of celebration. Although not designated as a gazetted holiday in Delhi and Haryana, Lohri is joyously commemorated by Sikhs, Hindus, and individuals from diverse backgrounds who wish to partake in its revelry.

While not officially observed in Punjab, Pakistan, the spirit of Lohri remains alive among Sikhs, Hindus, and some Muslims in rural Punjab, alongside pockets in Faisalabad and Lahore. Keeping this cultural tradition vibrant and thriving is deemed significant by individuals like Muhammad Tariq, the former director of Faisalabad Arts Council, emphasizing the shared celebration of Lohri in both Pakistani and Indian Punjabi cultures.

Yule

(Scandinavia, Germany, UK and other parts of Northern Europe)

Yule (also called Jul, jól or joulu) historically refers to a midwinter festival celebrated by various Germanic peoples and later adapted into Christmas traditions. The term "Yule" has Norse and Anglo-Saxon origins, and its significance has evolved over time. Originally, Yule was a pagan festival marking the winter solstice, typically observed around late December to early January in the Northern Hemisphere. It celebrated the return of longer days and the rebirth of the sun as the days began to lengthen after the shortest day of the year. Researchers have linked the ancient observances of Yule to the Wild Hunt, the deity Odin, and the pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon celebration known as Mōdraniht ("Mothers' Night"). Today, the term "Yule" and its counterparts persist in English, Scandinavian languages, Finnish, and Estonian, used to denote Christmas and similar festivals held during the winter season. Moreover, several contemporary Christmas practices - like the Yule log, Yule goat, Yule boar, Yule singing, among others - may trace their origins back to earlier pagan Yule customs.

The festival involved various customs and rituals, including feasting, burning of the Yule log, giving gifts, and decorating with evergreen plants like holly, mistletoe, and pine branches. These traditions were meant to symbolize hope, renewal, and the continuity of life during the dark and cold winter months. With the spread of Christianity in Europe, many pagan traditions were integrated or overlaid with Christian celebrations. Yule became assimilated into Christmas festivities, and many of its customs and symbols, such as the Yule log and decorations, were absorbed into the Christmas traditions we know today.

However, in modern times, some neo-pagan or contemporary pagan movements have revived the celebration of Yule as a distinct holiday, honoring its historical roots and celebrating the winter solstice as a time of spiritual significance, renewal, and connection to nature. For these groups, Yule often represents themes of rebirth, the return of light, and the cycle of nature.

Ziemassvētki

(Latvia)

Ziemassvētki, also referred to as Ziemsvētki, marks an annual celebration in Latvia, honoring both the winter solstice and the birth of Jesus Christ. Across Latvia and among Latvian communities worldwide, festivities span from December 24th to 25th. The 24th of December, known as Ziemassvētku vakars (Christmas Eve or Christmas Evening), sets the stage for the celebrations, while the subsequent days hold significance as Pirmie Ziemassvētki (First Christmas) on the 25th and Otrie Ziemassvētki (Second Christmas) on the 26th. Traditionally, Christianity observes Jesus Christ's birth on December 25th according to the Julian calendar. However, Orthodox churches, following the Eastern Orthodox liturgical calendar, celebrate Ziemassvētki on January 6th, 7th, and 8th.

Masque processions called budēļi, ķekatas, kaļadas in different parts of Latvia (source: letthejourneybegin.eu)

Beyond its Christian origins, Ziemassvētki transcends religious boundaries, embraced by people of various beliefs. It represents the traditional Christmas celebrations observed in Latvia, blending Christian customs with ancient pagan traditions rooted in Baltic folklore and beliefs. The origins of Ziemassvētki trace back to ancient Baltic pagan celebrations linked to the winter solstice, focusing on the transition from darkness to light, the rebirth of the sun, and the renewal of life. It dates back to ancient times in Latvia and is one of the oldest known celebrations in the Baltic region. It was traditionally celebrated by the indigenous Latvian pagans long before the arrival of Christianity. With the spread of Christianity, Ziemassvētki was absorbed into Christian celebrations and became associated with Christmas. However, many of the original pagan traditions and symbolism still persist in modern Latvian Christmas celebrations.

Contemporary Ziemassvētki customs include adorning the Ziemassvētku egle (Christmas tree), welcoming the Ziemassvētku vecītis (Santa Claus or Old Christmas Man), and indulging in the tradition of baking piparkūkas (gingerbread) while savoring the aroma of mandarins.

In summary, Ziemassvētki is an ancient Latvian celebration of the winter solstice, with deep roots in paganism and folklore. It reflects Latvia's rich cultural heritage, blending ancient pagan beliefs with Christian traditions, emphasizing the importance of family, community, and the seasonal cycle. The festival's customs and symbolism continue to resonate in modern Latvian holiday traditions.

_b_856_small.jpg)