Summer Solstice

The summer solstice is an astronomical event that occurs annually in the Northern Hemisphere around June 20th to 22nd, and in the Southern Hemisphere around December 20th to 22nd. It marks the longest day and shortest night of the year in the Northern Hemisphere, and the shortest day and longest night in the Southern Hemisphere.

The summer solstice happens because the Earth's axis is tilted relative to its orbit around the Sun. During the summer solstice in the Northern Hemisphere, the North Pole is tilted toward the Sun, resulting in the Sun reaching its highest point in the sky and providing the most daylight hours.

Many cultures and societies around the world celebrate the summer solstice with various traditions, festivals, and rituals. One of the most famous celebrations is the ancient festival of Stonehenge in England, where thousands of people gather to witness the sunrise aligning with the stones. In Scandinavia, the Midsummer Festival is a significant event with dancing, feasting, and other festivities.

The summer solstice has cultural, spiritual, and historical significance for many people and is often associated with themes of renewal, fertility, and the power of the Sun. It also marks an important milestone in the changing of seasons.

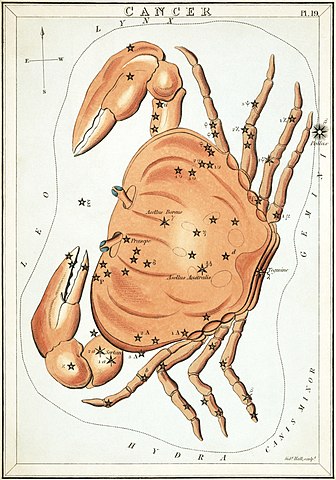

Astrological perspective

The Summer Solstice heralds the entry of the Sun into the zodiac sign of Cancer. Cancer is a water sign associated with emotions, nurturing, and the home. This transition brings a focus on family, emotional connections, and domestic matters. Cancer is ruled by the Moon, and it is known for its emotional depth and sensitivity. During the Summer Solstice, there may be a heightened awareness of emotions, intuition, and the need for nurturing and support. Cancer is often associated with the home and family life. The Summer Solstice can be a time for reconnecting with loved ones, strengthening family bonds, and creating a sense of emotional security within the home environment. Cancer is a Cardinal sign, which means it is associated with initiating energy, leadership, and new beginnings. The Summer Solstice marks the beginning of the summer season, and it's a time when many people feel inspired to set new intentions and embark on fresh endeavors.

Cancer as depicted in Urania's Mirror, a set of constellation cards published in London c.1825. (source: Wikipedia)

The Summer Solstice is a time of maximum light in the Northern Hemisphere. It symbolizes the peak of energy and vitality. It also serves as a reminder of the cyclical nature of life, with the days gradually getting shorter as we move towards the winter months. The heightened energy of the Summer Solstice can be harnessed for spiritual and personal growth. It's a time to explore inner wisdom, connect with higher consciousness, and seek balance between the inner and outer worlds. Astrologically, the Summer Solstice aligns with the power and energy of the Sun. It's a time to appreciate the life-giving force of the Sun and the abundance of nature during the summer season. The Summer Solstice is also a natural point for reflection, as it marks the halfway point of the solar year. It's a time to assess progress, set goals for the second half of the year, and consider areas of personal growth and development.

Various celebrations and traditions associated with the Summer Solstice

Here is a list of various celebrations and traditions associated with the Summer Solstice from cultures around the world:

-

Drăgaica and Sânzienele (Romania)

Drăgaica and Sânzienele are two names for a pre-Christian midsummer fertility ritual, celebrated on June 24, closely tied to summer solstice festivities.

-

Duanwu Festival (China)

The Duanwu Festival, also known as the Dragon Boat Festival, usually falls around the time of the summer solstice. It involves dragon boat races, eating zongzi (sticky rice dumplings), and wearing colorful silk threads to ward off evil spirits.

-

Kupala Night (Slavic community)

Kupala Night is a Slavic folk celebration that takes place on the Summer Solstice. It combines elements of pre-Christian pagan rituals with Christian traditions. People gather around bonfires, jump over fires, and search for the mythical "fern flower" which is said to bring good luck.

-

Jāņi (Latvia)

Jāņi is a yearly Latvian celebration that honors the summer solstice. The eve before Jāņi is referred to as Līgosvētki, Līgovakars, or simply Līgo.

-

Joninės (Lithuania)

Joninės is a Lithuanian holiday marking the summer solstice, celebrated with bonfires, rituals, and traditional folk festivities.

-

Jónsmessa (Iceland)

Jónsmessa is an Icelandic midsummer celebration, linked to folklore beliefs, celebrated on June 24th, marked by bonfires and traditional customs, believed to possess magical properties for healing and fortune.

-

Klidonas (Greece)

In some parts of Greece, particularly in rural areas, the Summer Solstice is celebrated with the Klidonas festival. It involves rituals to purify and protect against evil spirits. Young people jump over bonfires, and a game is played where unmarried girls place herbs in water to find out about their future husbands.

-

Kresna noč or Kresnikova noč (Slovenia, the Istrian part of Croatia)

Similar as Kupalo in other Slavic countries, Kresna night (Kresna noč) is one of the most preserved traditional holidays. It is also one of the most important folk holidays. Bonfire evening marks the beginning of summer. It dates back to times long before Christianization.

-

Kronia (Ancient Greece)

The festival of Kronia honored Cronus, and the ancient Greeks celebrated the summer solstice with feasting, sports, and honoring the gods.

-

Midsummer Night in honor of goddess Áine (Ireland)

Midsummer Night is a celebration in Ireland honoring the goddess Áine, marked by bonfires, rituals, and festivities on the eve of the summer solstice, having ties to ancient pagan traditions associated with fertility, abundance, and protection.

-

Saint John's Eve (Christian Community)

Saint John's Eve, celebrated on June 23rd, marks the eve of the feast day of St. John the Baptist, observed with bonfires, rituals, and cultural festivities across many countries, intertwining Christian customs with ancient pagan traditions tied to the summer solstice.

-

Sun Dance (Natives of North America)

Various Native American tribes hold ceremonies and dances to honor the Sun and celebrate the summer solstice. These ceremonies vary among tribes but often involve music, dance, and rituals to express gratitude for the Sun's energy and life-giving power.

-

Tekufat Tammuz (Judaism)

Tekufat Tammuz represents the summer solstice in the Jewish calendar, highlighting the longest day and shortest night of the year, observed with spiritual reflection and connections to seasonal changes.

-

Tirgān (Iran)

Tiregān is a Persian festival celebrated on the 13th day of the month of Tir (3rd, 4th of June in Gregorian calendar) in the Iranian calendar, marking the beginning of summer, observed with outdoor gatherings, picnics, and joyful festivities rooted in ancient traditions and cultural heritage.

-

Ukko's celebration - Ukon juhla (Finland)

Ukon juhla is a Finnish celebration dedicated to Ukko, the ancient god of thunder and crops, typically observed around the summer solstice, involving rituals, bonfires, and festivities to honor nature and ensure a bountiful harvest.

-

Vestalia (Ancient Rome)

The ancient Romans celebrated the summer solstice with festivals like Vestalia, honoring gods like Vesta.

Vestalia was an ancient Roman festival held in honor of Vesta, goddess of the hearth, observed during mid-June with rituals, offerings, and purification of the temples, emphasizing domestic and communal well-being.

-

Xiazhi (China)

Xiazhi is a traditional Chinese term referring to the summer solstice, symbolizing the peak of yang energy, often marked with special foods like noodles, dumplings, and seasonal fruits, along with various cultural and health-related practices to align with the season's energy.

-

Yhyakh (Yakuts)

Yhyakh is a traditional Yakut festival celebrated in Siberia during the summer solstice, involving cultural performances, rituals, horse races, and communal feasts to honor nature, ancestors, and the start of the summer season.

Drăgaica and Sânzienele

(Romania)

Drăgaica and Sânzienele represent a pre-Christian midsummer fertility ritual, observed on June 24th. Drăgaica, associated with areas influenced by Thracian/Dacian culture like Dobrogea, Muntenia, and parts of Oltenia, derives from the Slavic girl's name Draga. Conversely, Sânzienele, more prevalent in Transylvania, Oltenia, Banat, and the Carpathians, stems from "Sancta Diana," the Latin moniker for the Roman goddess of the hunt and moon, protector of virgins. Drăgaica embodies the essence of the lunar, equinoctial, and agrarian Neolithic Goddess, evolving into revered figures like Hera, Artemis, Diana, and Juno in the Greek and Roman pantheons.

Sânziànă and Drăgaica refer to yellow flowers (Galium verum and Cruciata laevipes) that blossom during this period and play a role in the related rituals. These names also denote typically benevolent fairies, prevalent during this season, and are linked to young girls who symbolize these fairies in ceremonial practices.

The night of Sânziene Eve (from June 23rd to June 24th) holds mystical significance, representing nature's pinnacle and its most potent energy. It's believed to be a time for miracles, as the heavens are thought to open up, rendering it the most powerful night for casting magic spells, particularly those associated with love. Additionally, plants harvested during this period are said to possess remarkable magical properties.

According to peasant tales, Sânzienele are depicted as fairies or nymphs who, by night, transform into fair-haired beauties, dancing beneath the moonlight. They traverse the land, singing and bestowing fertility upon crops, married couples, birds, and animals, while also healing the ill and safeguarding cultivated fields from hail. However, failing to honor them properly with respect and gratitude might provoke their ire, leading to potential retribution.

According to tradition, the day following is revered as the quintessential summer day, with the Sun reigning high in the sky. On this day, village maidens, adorned in white attire, spend their time gathering flowers to weave into floral crowns. Among them, one is selected as the Drăgaica, adorned with a wheat wreath symbolizing a bride, while the others wear white veils adorned with Sânziànă flowers. As evening falls, they return to the village, rendezvous with their beloved, and dance around a bonfire. Jumping over the embers is believed to purify and bring forth good health.

Numerous Romanian villages and cities host Midsummer fairs. Among them, the most renowned and ancient is the Drăgaica fair held in Buzău.

Duanwu Festival

(China)

The Duanwu Festival, also known as the Dragon Boat Festival, has ties to the summer solstice, although its origins are multifaceted and not solely linked to this celestial event.

The festival is primarily associated with Qu Yuan, a revered poet and statesman during China's Warring States period. He was known for his loyalty to his kingdom of Chu and his poetic prowess. Distressed by political corruption, he drowned himself in the Miluo River on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month (around the summer solstice) in 278 BCE. Local fishermen attempted to save Qu Yuan by racing their boats and throwing rice into the river to distract fish from consuming his body. This is said to be the origin of dragon boat races during the festival.

The Duanwu Festival is a fusion of historical events, including Qu Yuan's sacrifice, and the ancient Chinese cultural beliefs tied to the summer solstice. The fifth day of the fifth lunar month typically falls close to the summer solstice in the northern hemisphere, signifying the sun's peak strength and the longest daylight hours. The festival represents a time of celebrating nature's vitality and the approaching summer harvest season, aligning with the solstice's themes of abundance and agricultural significance.

Kupala Night

(Russia)

Kupala Night, also known as Ivan Kupala Day, is a Slavic celebration tied to the summer solstice, combining pre-Christian pagan customs with Christian influences.

Kupala Night has deep roots in ancient pagan beliefs celebrating the summer solstice, honoring the sun's power, fertility, and the vitality of nature. The celebration was dedicated to pagan gods and goddesses like Kupala (also known as Kupalo or Ivan Kupala), associated with the sun, fire, and fertility.

Jumping over a bonfire is one of the main events of Ivana-Kupala celebrations. According to tradition, it is a test of bravery but also a process of purification. Romantic couples jump over the bonfire holding hands. Failure to do so means a separation in the future. (source: rferl.org)

Central to the celebration are large bonfires, symbolizing the sun's strength. People leaped over the flames, seeking blessings and purification. Many rituals involved water, such as swimming in rivers or lakes, symbolizing purification and fertility. Young couples often jumped over fires and then into the water together. Creating and wearing flower wreaths, floating them on water, or releasing them into rivers were common practices, symbolizing love, fortune, and divination. There were beliefs in the magical properties of herbs gathered on Kupala Night, used for healing, protection, and fortune-telling.

With the spread of Christianity, pagan festivals were often adapted to Christian feasts. Kupala Night coincided with the feast of John the Baptist (St. John's Day) on June 24th, aligning with the summer solstice. Some traditions associated with Kupala Night merged with Christian celebrations of St. John the Baptist, incorporating elements like bonfires and water-related rituals.

Kupala Night's celebrations reflect a blending of ancient pagan rituals honoring the summer solstice with later Christian influences. Today, it remains an occasion for cultural festivities, music, dance, and reconnecting with Slavic heritage and traditions.

Jāņi

(Latvia)

Jāņi is a Latvian celebration deeply rooted in ancient pagan traditions and closely tied to the summer solstice. Jāņi is fundamentally a celebration of the summer solstice, an important time in ancient pagan beliefs symbolizing the peak of the sun's power and the longest day of the year. The festival honors nature's fertility, the abundance of the earth, and the cycle of growth and harvest. It's a time to celebrate the vitality of crops and life.

A man with an oak leaf wreath lighting up a pūdele (a container filled with tar, decorated with oak leaves and attached atop of a pole). (source: Wikipedia)

Lighting bonfires holds significant symbolism, representing the sun's strength and protection against evil spirits. People jump over the flames, seeking luck and purification. Gathering and using specific herbs, especially those believed to possess magical or healing properties, are integral to Jāņi rituals. Making and wearing flower wreaths and singing traditional folk songs are common practices, symbolizing the beauty of nature and community unity.

Jāņi in Latvia maintains a blend of ancient pagan traditions and Christian elements, symbolizing the summer solstice's significance while celebrating nature's bounty, community, and the joys of the season. It stands as a cultural celebration deeply rooted in Latvia's heritage and beliefs.

Joninės

(Lithuania)

Joninės, also known as Rasos or Midsummer Day in Lithuania, is a festival deeply connected to ancient pagan traditions and the summer solstice. Joninės is rooted in pagan rituals celebrating the summer solstice, marking the longest day of the year and the peak of the sun's power. It's a time to honor nature's fertility, symbolizing the vitality of crops, growth, and the abundance of the earth.

Lighting large bonfires holds great significance, representing the sun's energy and protection against evil spirits. People leap over the flames for purification and good fortune. Gathering and utilizing specific herbs, especially those believed to have magical or healing properties, are integral to Joninės rituals. Making and wearing flower wreaths, singing traditional songs, and participating in folk dances celebrate the beauty of nature and community bonding.

Joninės in Lithuania maintains a fusion of ancient pagan traditions and Christian elements, representing the significance of the summer solstice while celebrating nature's abundance, community, and the beauty of Lithuanian cultural heritage.

Jónsmessa

(Iceland)

Jónsmessa is an Icelandic celebration connected to the summer solstice and has roots in ancient pagan beliefs. Jónsmessa originates from pagan traditions celebrating the summer solstice, marking the longest day of the year when the sun reaches its zenith. The festival honors nature's vitality, fertility, and the abundance of light during this period.

Lighting bonfires holds symbolic importance, representing the sun's strength and protection against evil spirits. Leaping over the flames was believed to bring blessings and cleanse one's spirit. Collecting and using specific herbs, especially those deemed magical or healing, were customary during Jónsmessa, believed to have increased potency on this night. Various superstitions and folk beliefs surround Jónsmessa, such as the belief that cows gain the ability to speak at midnight.

Jónsmessa in Iceland blends ancient pagan customs with Christian influences, signifying the summer solstice's significance while celebrating nature's bounty, community, and the spirit of Icelandic cultural heritage.

Klidonas

(Greece)

Klidonas is a Greek tradition closely tied to the summer solstice, originating from ancient pagan customs and beliefs. Klidonas is rooted in pagan rituals honoring the summer solstice, a time representing the sun's peak strength and the longest day of the year. The festival was associated with fertility rites, warding off evil spirits, and superstitions to ensure good fortune. Lighting fires played a significant role, symbolizing the sun's power and warding off malevolent forces. People leaped over flames for purification and blessings. Immersing objects, particularly personal belongings or small items, into water sources like springs or fountains was believed to bring good luck and health. Various divination rituals, such as using melted lead to foretell the future, were common practices during Klidonas.

The word "Klidonas" came from the ancient word “klidon” that means a forecasting sound, a sound of a prophetic sign. Klidonas is a popular prophetic process during which the unmarried girls get to know to whom and when they will get married.

On the eve of Agios Ioannis celebration, occurring on June 24th, unmarried women gather in a village. They select one to fetch the "amilito nero," the silent water, from the local well or spring. The spring water is collected in a clay pot, with each girl placing an item, a "rizikari," inside. After all have contributed, the pot is covered with red cloth, tied with a cord, and left outdoors overnight under the stars' influence. The following day, a gathering convenes to witness the prophetic ritual. The girl who fetched the "amilito nero" removes the objects from the clay pot. A Cretan folk couplet, a mantinada, accompanies each object, revealing its owner's future. Once done, the girl empties the pot's water into the well, covering it with cloth. Then, she unveils it, allowing the sun or moon's rays to reflect in the well. Meanwhile, the other girls toss their items into the well, while young men and women observe the water's ripples, seeking glimpses of their future.

Klidonas in Greece blends ancient pagan customs with Christian elements, marking the summer solstice's importance while celebrating nature's abundance, cultural heritage, and the customs passed down through generations.

Kresna noč or Kresnikova noč

(Slovenia, the Istrian part of Croatia)

Kresna noč is one of the biggest fire festivals, marking the beginning of the period when sunlight begins to wane. In Old Slavic mythology, Kresnik was the golden-haired and golden-armed son of the fire god who inherited the sun, light, heat and fire. Kresnik was originally a solar deity, which was later adapted by Christianity to its needs and supplanted by the worship of St. John the Baptist. So in the end, only a name remained of Kresnik. In some places, so-called Saint John's bonfires are still burning today, which is undoubtedly a remnant of pagan bonfires and the Old Slavic Kresnik mythological cycle.

The saying "The day hangs on a bonfire" ("O kresi se dan obesi") still reminds us of the fact that after the summer solstice, when the sun stands still, the days begin to shorten.

By lighting bonfires on high hills and mountains, as close as possible to the sky, the sun should receive as much light and heat as possible and continue to shine with full power for a long time. That is why the night of bonfire is also called the "Night of the Big Fire". In some places, oak stumps were burned on fireplaces. People used to jump over the fire at bonfires. They also danced and sang around the fire. Livestock were driven through fire to cleanse themselves of disease and evil forces. When the fires burned down, they carried the remaining ashes home, sprinkled them in all corners of the house, scattered them on the fields, and sometimes placed the embers on their hearts. This ash is said to have the power of protection, to ensure health and happiness.

During the Midsummer Night, in addition to summoning a good harvest to the fields, it is possible to find treasure or summon the devil, find out about your future and even hear and understand the language of animals. This magical night, which has great power in it, is associated with fairy-tale creatures such as witches, fairies, dwarfs and other supernatural fairy-tale creatures. The deep belief in the sanctity of the bonfire is also evidenced by the old story about the bonfire, when it was not possible to light the fire, it did not want to burn, and a certain farmer got angry and swore: "Devil, won't it burn?!" In that one, a strong wind blew, which blew the fire all over the village. To prevent the entire village from burning down, they had to extinguish it with holy water.

Midsummer night, according to popular belief, is also the most suitable time for gathering magical plants, herbs and flowers. Plants gathered on this night have a very special power. Sometimes they were picked before dawn, when there was still dew on them. Collected plants were hung on doors, windows and around homes for protection, and were even placed in the spouses' beds. They used them to decorate the house and the barn on Midsummer Eve, so that people and livestock would be healthy and protected. Women also threw bonfire flowers into the fire, by which they then warmed themselves, as the charm of the plants was said to give them an easier birth.

Women wore wreaths woven from clover and other plants, and men wore wreaths made from oak leaves and plants. Livestock were also decorated with wreaths made of greenery gathered during the Midsummer night. Even the Old Slovene name for the month of June – rožnik, the month of flowers – testifies that nature is in full bloom during this period. Most of the magic on Midsummer Night can definitely be attributed to the fern. Fern seed has a special power, especially if those who collected it were naked and if the fern grew at a crossroads. They washed themselves with fern water and thereby protected themselves from diseases and evil forces. The magic seed is supposed to make you invisible, help against spells, protect you from lightning. Fern seeds were carried in pockets, sewn into skirts, hats, scarves. If a girl carried a seed in her bosom, then she was sure to have a boy, but if someone unknowingly got a fern seed in his shoe on Midsummer Eve, he could understand animal language.

The magical power of the fern is also told in an old Slovenian tale about a servant who fell asleep on the litter in the stable on Midsummer's Eve and did not know that he had a miraculous fern seed with him. When he woke up, he heard the story of the oldest ox in the barn that in the spring the master would be bitten by a poisonous snake and that he, the old ox, would be sold this year. The servant was therefore always on the lookout during the spring and managed to kill the snake before it managed to bite the master. The old ox was indeed sold. If someone succeeds in uprooting a fern at exactly midnight, they get a golden ring at the end of the root. In some places, it was believed that Saint John himself would sleep on a fern during his journey during the Midsummer Night.

Another important bonfire plant and flower of the sun is the St. John's wort, which begins to bloom at the time of the bonfire night. Its very name, which reminds us of St. John, tells us that it is time to harvest it. Its golden yellow blossoms resemble the sun. The ancients strongly believed in its protective and defensive power. On Midsummer's Eve, when summer begins and with it the danger of severe weather, it was attached to the windows so that lightning would not hit the house.

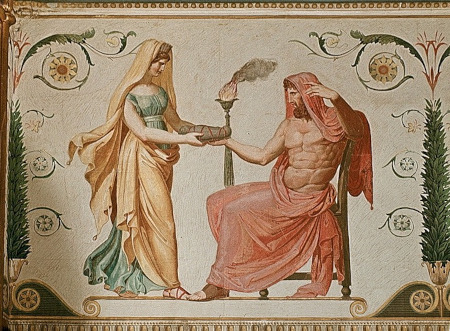

Kronia

(Ancient Greece)

Kronia was an ancient Greek festival observed in honor of god Kronos or Cronus, associated with agriculture, time, and the harvest. While not specifically tied to the summer solstice, Kronia did align with the agricultural calendar and could have taken place around the summer months.

Rhea giving the rock to Cronus, 19th-century painted frieze by Karl Friedrich Schinkel (source: wikipedia)

The festival paid homage to Kronos, revered as a deity linked to agriculture, the cycle of time, and the abundance of the harvest. As an agricultural festival, it likely centered on acknowledging the harvest's importance and seeking blessings for a bountiful yield.

"Kronia - 12th The Kronia is a festival in honor of Kronos as a god of the grain harvest, who is depicted with a reaping hook; on this day a harvest supper celebrates the final end of the harvest. More broadly it is (like the Saturnalia) a celebration of the Golden Age ruled by Kronos and Rhea, when there was no labor or oppression. Since this was before Zeus brought order to the world, the Kronia is a chaotic festival. In ancient times, slaves were allowed to run riot in the streets, and were invited to sumptuous banquets by their masters. During the Kronia we are allowed a temporary return to the Golden Age, to equality, luxury, ease and unconstrained freedom."

Kronia involved communal feasting, celebrations, and possibly activities that allowed slaves or servants to participate alongside their masters, symbolizing a temporary social equality. Offerings might have been made to Cronus, along with rituals seeking his favor for a fruitful harvest season.

While not exclusively a solstice festival, Kronia possibly fell within the broader context of seasonal celebrations, potentially occurring around the summer months, emphasizing the significance of agricultural cycles.

Midsummer Night in honor of goddess Áine

(Ireland)

Midsummer Night in Ireland, honoring the goddess Áine, intertwines Celtic mythology and the celebration of the summer solstice. Áine is an Irish goddess of summer, wealth, fertility, sovereignty and the land's abundance. She is associated with midsummer and the sun, and is sometimes represented by a red mare. Midsummer Night, occurring around the summer solstice, was an occasion to honor Áine and celebrate the sun's peak power and the longest day of the year.

Lighting of bonfires, a central aspect of the celebration, symbolized the sun's energy and protection against malevolent forces. People leaped over the flames for purification and blessings. Gathering magical plants and herbs on Midsummer Night held significance, believed to possess heightened powers. Divination rituals might have been performed to glimpse the future.

Saint John's Eve

(Christian Community)

Saint John's Eve, commencing at sundown on June 23rd, heralds the eve of Saint John the Baptist's feast day - a rare celebration commemorating a saint's birth rather than their passing. According to the Gospel of Luke (Luke 1:26–37, 56–57), John's birth, occurring six months before Jesus', led to the establishment of his feast on June 24th, precisely six months prior to Christmas. This date aligns with the summer solstice in the Roman calendar, intertwining Saint John's Eve with Midsummer revelries across Europe. The customs mirror those of May Day, encompassing vibrant bonfires (known as St. John's fires), communal feasts, lively processions, church ceremonies, and the collection of untamed flora.

Manuscript Illumination with Scenes from the Life of Saint John the Baptist, South Netherlandish, Master of James IV of Scotland (probably Gerard Horenbout) (source: wikipedia)

Saint John's Day, dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, was officially recognized by the unified Christian Church during the 4th century A.D. in honour of the saint's birth.

"Christ's Incarnation was closely tied to the 'growing days' (diebus crescentibus) of the solar cycle around which the Roman year was based. By the sixth century, this solar cycle was completed by balancing Christ's conception and birth against the conception and birth of his cousin, John the Baptist. Such a relationship between Christ and his cousin was amply justified by the imagery of scripture. The Baptist was conceived six months before Christ (Luke 1:76); he was not himself the light, but was to give testimony concerning the light (John 1:8–9). Thus John's conception was celebrated on the eighth kalends of October (24 September: near the autumn equinox) and his birth on the eighth kalends of July (24 June: near the Summer solstice). If Christ's conception and birth took place on the 'growing days', it was fitting that John the Baptist's should take place on the 'lessening days' (diebus decrescentibus), for the Baptist himself had proclaimed that 'he must increase; but I must decrease' (John 3:30). By the late sixth century, the Nativity of John the Baptist (24 June) had become an important feast, counterbalancing at midsummer the midwinter feast of Christmas."

In Christian theology, John the Baptist was seen as the forerunner to Jesus, as indicated in John 3:30 with the phrase "He must increase, but I must decrease." This concept is represented by the sun's diminishing height in the sky and the shorter days following the summer solstice, symbolizing decrease, followed by its increase after the winter solstice.

Several summer solstice celebrations were Christianized over time, incorporating Christian elements into earlier pagan festivities. Here are some examples:

-

Brazil: Festas Juninas, also known as festas de São João

-

Cornwall: Golowan

-

Croatia: Ivanjski krijesovi, Ivanjdan or Svitnjak

-

Denmark: Sankt Hans Aften

-

Estonia: Jaanipäev, Jaaniõhtu

-

Finland: Juhannus

-

France: Fête de la Saint-Jean

-

Latvia: Jāņi

-

Lithuania: Joninės

-

Norway: Jonsok

-

Poland: Noc Świętojańska or Wianki

-

Spain: Fiesta de San Juan, Dia de San Juan or Noche de San Juan

-

Sweden: Midsommar, Midsommarafton or Jonsok

Sun Dance

(Natives of North America)

The Sun Dance is a ceremonial practice observed by select Native American communities in the United States and Indigenous groups in Canada, notably among Plains cultures. It typically entails communal gatherings aimed at collective healing through prayer. During this ritual, individuals undertake personal sacrifices as offerings for the well-being of the community.

The ceremonies observed by Sun Dance cultures share several common elements passed down through generations. These include traditional dances and songs, the use of ceremonial drums, a sacred fire, prayer with a ceremonial pipe, fasting before the dance, and sometimes ceremonial skin piercing coupled with endurance trials. Specific plants are gathered and readied for ceremonial use.

The Sun Dance is an arduous trial for participants, serving as both a physical and spiritual test that they willingly endure as a sacrifice for their community. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, young men are tethered by "rawhide thongs pegged through the skin of their chests" while dancing around a pole, although not all ceremonies involve piercing. The primary aim of the Sun Dance is personal sacrifice for the betterment of one's family and community. Dancers endure long periods of fasting in the open air, facing the elements.

During these ceremonies, friends and family members remain in surrounding camps, offering prayers in support of the dancers. The entire community invests significant time and effort to orchestrate the Sun Dance, often planning and preparing for up to a year in advance. While one or a few leaders typically oversee the ceremony, many elders offer guidance, and a team of helpers manages the necessary preparations.

While the Sun Dance and the summer solstice are distinct in their cultural contexts and practices, they share overarching themes of cosmic rhythms, spiritual renewal, and the profound relationship between humanity and the natural world. Both symbolize the cyclical nature of life, emphasizing unity, healing, and the continuous cycles of growth and change.

Tekufat Tammuz

(Judaism)

Tekufat Tammuz refers to the astronomical event in the Jewish calendar, marking the summer solstice in the Northern Hemisphere. This term isn't solely tied to a religious or ceremonial observance but rather signifies a specific moment in time, aligning with the changing seasons.

Tekufat Tammuz marks the point in the solar calendar when the sun reaches its northernmost point, resulting in the longest day and shortest night of the year in the Northern Hemisphere. This event signifies the beginning of summer, representing a pivotal moment in the celestial cycle and the transition to warmer, sunnier days.

In the Jewish calendar, Tekufat Tammuz is one of the four seasonal markers known as tekufot, delineating the solstices and equinoxes. While the event itself isn't a religious observance, its timing might hold cultural or historical significance for some Jewish communities.

Tirgān

(Iran)

Tirgān, also known as Jashn-e Tiregān, is an ancient Persian festival celebrated in Iran, rooted in pre-Islamic traditions. This festival has historical significance and traces back to the Zoroastrian era, emphasizing themes of joy, rejuvenation, and the triumph of light over darkness.

Tirgān predates Islam and has its origins in Zoroastrianism, an ancient Persian religion. It commemorates Tir, the Zoroastrian angel of rain, whose name is associated with rain and fertility, essential for agriculture and prosperity.

Celebrated on the 13th day of the month of Tir in the Iranian calendar, which usually falls in late June or early July, close to the summer solstice. Tirgān honors nature, abundance, and fertility, reflecting the reverence for the elements, particularly water, and its role in agriculture.

People gather in parks or gardens, enjoying outdoor picnics, music, dancing, and feasting. Water plays a significant role; people might sprinkle water or splash each other in a symbolic gesture of promoting rain and prosperity. Some traditions involve tying colorful ribbons to trees as a wish for health and good fortune.

Despite historical and religious changes in Iran, Tirgān continues to hold cultural significance. It's celebrated by Iranians, although its observance might vary among regions and communities. In recent years, efforts have been made to revive and promote Tirgān, recognizing its historical and cultural importance in Iran's heritage.

Tirgān stands as a cultural vestige, preserving ancient customs and traditions, offering a glimpse into Iran's pre-Islamic history and its rich cultural tapestry. While its observance has evolved over time, it remains a cherished celebration, reflecting reverence for nature, fertility, and the triumph of life and abundance.

Ukko's celebration - Ukon juhla

(Finland)

Ukon juhla, or Ukko's celebration, has historical roots in Finnish pagan traditions, particularly centered around the worship of Ukko, the chief god in Finnish mythology associated with the sky, thunder, and weather.

Ukon juhla traces back to pre-Christian times when the ancient Finns revered Ukko as the principal deity, symbolizing thunder, fertility, and protection. The celebration often coincided with the agricultural calendar, marking key moments in planting or harvest seasons, particularly tied to ensuring good weather for crops.

Painting by Robert Ekman in 1867 called Lemminkäinen tulisella järvellä where Lemminkäinen asks help from Ukko ylijumala with crossing the lake in fire on his route to the wedding at Pohjola. (source: wikipedia)

The exact date of Ukon juhla varied but typically occurred during the summer months, possibly close to the summer solstice, echoing the celebration of light and warmth. Celebrations involved rituals, offerings, and communal gatherings to honor Ukko, often including prayers for favorable weather, agricultural prosperity, and protection.

Lighting bonfires was common, symbolizing purification, warding off evil spirits, and invoking Ukko's blessings. Offerings such as food, drink, or symbolic items were made to Ukko, seeking his favor for bountiful harvests and protection.

With the spread of Christianity, pagan traditions like Ukon juhla gradually merged or transformed into Christianized festivals or were discontinued. In contemporary Finland, efforts to revive and reconnect with pre-Christian heritage have led to renewed interest in ancient customs, including reviving or acknowledging celebrations like Ukon juhla.

Ukon juhla reflects ancient Finnish pagan beliefs and practices, emphasizing reverence for Ukko and nature's forces. While the celebration's observance might have evolved or diminished over time due to religious changes, it remains a part of Finland's cultural heritage, representing the country's deep-rooted pagan past and its connections to nature, agriculture, and the divine.

Vestalia

(Ancient Rome)

Vestalia was an ancient Roman festival dedicated to Vesta, the goddess of the hearth, home, and family. It was celebrated annually from June 7th to June 15th. While Vestalia isn't directly tied to the summer solstice, its timing coincides with the beginning of summer in the Northern Hemisphere, albeit slightly before the solstice.

Rare depiction of Vesta in human form, as the central figure from the Lararium of a bakery at Pompeii, 1st century (source: wikipedia)

Vesta was highly revered as the guardian of the sacred fire, symbolizing both the hearth in homes and the eternal flame in her temple in Rome. Vestalia honored Vesta's role in preserving the family, domesticity, and the sacred fire that signified warmth, nourishment, and continuity.

The festival commenced with the opening of Vesta's temple, usually closed to the public. While some ceremonies were held within the temple, others took place in private homes, focusing on purifying the hearth and invoking blessings for family well-being. Offerings, prayers, and processions honored Vesta, seeking her protection and favor for the city and its inhabitants.

A key ritual during Vestalia was the Penus Vestae, where the sacred fire of Vesta's temple was symbolically renewed. The temple's eternal flame was of paramount importance, and its maintenance was essential for Rome's well-being. During Vestalia, the focus was on ensuring its perpetual burning and purity.

Vestalia served as a significant festival in ancient Rome, dedicated to Vesta, the goddess of the hearth and family. It underscored the importance of domestic harmony, the sacredness of the hearth, and the enduring flame in Vesta's temple, reflecting Roman reverence for home, community, and continuity through rituals and offerings to honor the goddess. Both Vestalia and the solstice share thematic elements of light, renewal, and the significance of the changing seasons, contributing to the cultural and symbolic richness of this period in ancient Roman tradition.

Xiazhi

(China)

Xiazhi, also known as "Xia Zhi" or "Summer Solstice" in Chinese, is a traditional East Asian festival marking the peak of summer and the longest day of the year in terms of daylight hours. Xiàzhì marks the 10th solar term, signifying the summer solstice in the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar, which divides the year into 24 solar terms. It commences as the Sun reaches a celestial longitude of 90° and concludes at 105°. The term "xiazhi" specifically denotes the day when the Sun aligns precisely at the celestial longitude of 90°, typically around June 21st in the Gregorian calendar. This period extends until the commencement of the subsequent solar term, Xiaoshu, approximately on July 7th. Xiàzhì denotes the middle of summer, marking the onset of the hottest phase of the season. While once marked by traditional customs, these observances have dwindled, resulting in limited contemporary recognition of Xiazhi.

Xiazhi has roots in ancient agricultural practices, recognizing the sun's extreme zenith and its impact on crops during this pivotal period.It honors the sun's power and influence on agricultural cycles, highlighting gratitude for its role in promoting growth and vitality in crops. Xiazhi corresponds directly to the astronomical event of the summer solstice when the sun reaches its highest point in the sky, resulting in the longest daylight hours. In traditional Chinese philosophy (Yin-Yang theory), the summer solstice embodies the height of Yang energy, associated with brightness, warmth, and masculine attributes.

Xiazhi, tracing its origins to the Han dynasty, was once an ancient festival observed in China. During this time, people marked Xiazhi by taking a brief hiatus for merry-making and indulgence in food and drink. While government officials were granted respite, farmers persisted with their essential tasks. Compared to the grandeur of Dongzhi (the winter solstice celebrated with the Dongzhi Festival), Xiazhi held lesser importance in ancient China, resulting in simpler and less elaborate celebrations. Notably, during the Song dynasty, historian Pang Yuanying mentioned a three-day holiday for Xiazhi, whereas Dongzhi extended to a weeklong festivity. According to Liang dynasty scholar Zong Lin, farmers traditionally engaged in burning chrysanthemum leaves during Xiazhi, utilizing their ashes to safeguard wheat plants from diseases and pests, employing this natural method as a form of disinfection.

The Xiazhi "Nine Nines Song" (九九歌; Jiǔ Jiǔ Gē):

"一九二九扇子不离手;

三九二十七,饮水甜如蜜;

四九三十六,拭汗如出浴;

五九四十五,头带黄叶舞;

六九五十四,乘凉入佛寺;

七九六十三,床头寻被单;

八九七十二,思量盖夹被;

九九八十一,家家打炭基;

准备过冬了。"

Translation:

One nine, two nines, the fan doesn't leave your hand;

Three nines, twenty-seven, drinking water is as sweet as honey;

Four nines, thirty-six, wiping away sweat is like coming out of a bath;

Five nines, forty-five, yellow leaves dance above;

Six nines, fifty-four, cool off in a Buddhist temple;

Seven nines, sixty-three, look for the sheets at the bedside;

Eight nines, seventy-two, think about using a blanket;

Nine nines, eighty-one, every household makes charcoal;

Get ready for winter.

Families often come together to celebrate and enjoy meals, signifying unity and the importance of familial bonds. In some regions, Xiazhi coincides with the Dragon Boat Festival (Duanwu), known for dragon boat races, eating zongzi (sticky rice dumplings), and honoring Qu Yuan, a patriotic poet.

While Xiazhi's agricultural significance has diminished in modern times, its observance has evolved into a day for family reunions, cultural festivities, and relaxation.

Xiazhi, or the Summer Solstice in Chinese tradition, historically carried agricultural significance, emphasizing the sun's pivotal role in the growing season. While its direct agricultural associations might have lessened in contemporary times, it remains a cultural touchpoint for family gatherings and acknowledges the celestial transition marking the peak of summer.

Yhyakh

(Yakuts)

Yhyakh is a traditional festival celebrated by the Turkic and Yakut people, marking the summer solstice and embodying the vibrant spirit of summer. Yhyаkh, known in Yakut as Ыһыах [ɯhɯaχ], is a festival heralding nature's rejuvenation post the harsh winter, heralding life's victory and the commencement of a new year in the Sakha Republic. Traditionally observed on June 21st, it aligns with the summer solstice, symbolizing the peak of sunlight and the season's renewal.

The Yhyakh festival, denoting "abundance," holds ties to a solar deity and a fertility cult. Among the ancient Sakha traditions, Yhyakh marked the New Year celebration. Customs involved women and children adorning trees and poles with "salama" (nine bundles of horsehair suspended on horsehair ropes). Commencing the festivities, the eldest man clad in white initiates the ritual. He begins by sprinkling kymys on the ground, tending to the fire, and offering prayers to the Ai-ii spirits for the welfare of their people, seeking blessings for the assembled gathering.

Following these rituals, participants engage in Ohuakhai songs and dances, partake in indigenous games, savor local cuisine, and indulge in kymys, a traditional beverage.

Yhyakh fosters community unity, bringing people together for joyous gatherings, performances, and various festivities. Celebrations often include vibrant music, dance, rituals, and competitions, showcasing cultural heritage and skills.

Yhyakh involves prayers and offerings to honor nature, seeking blessings for bountiful harvests, good health, and prosperity. Horse-related events like races or displays of horsemanship are integral parts of the festivities, reflecting the nomadic heritage.

Despite changes over time, efforts persist to uphold Yhyakh's traditions, preserving cultural identity and connecting present generations with their ancestral practices. While maintaining core elements, modern Yhyakh celebrations often blend traditional customs with contemporary performances and activities.

Yhyakh stands as a vibrant celebration among Turkic and Yakut communities, embracing the summer solstice with cultural pride, communal togetherness, and reverence for nature's abundance. It reflects a blend of ancient traditions and contemporary expressions, fostering a deep connection between people, their heritage, and the changing seasons.