Spring Equinox

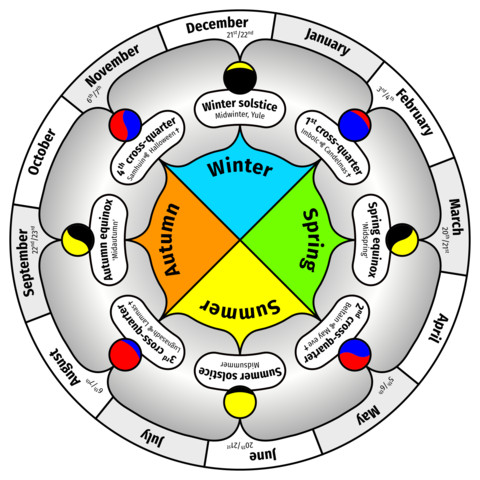

The Spring Equinox, also known as the vernal equinox or northward equinox, is an astronomical event that occurs around March 20-21 in the Northern Hemisphere. This event marks a specific moment in time when the center of the Sun appears to cross the celestial equator, an imaginary line in the sky above the Earth's equator.

To understand the equinox, it's important to be familiar with the celestial coordinate system. This is an imaginary grid used by astronomers to locate objects in the sky. The two main coordinates are Right Ascension (RA) and Declination (Dec), similar to longitude and latitude on Earth. The celestial equator is an imaginary circle in the sky, directly above the Earth's equator. It divides the celestial sphere into northern and southern hemispheres, much like the Earth's equator divides it into northern and southern halves. The Earth's axis is tilted at approximately 23.5 degrees relative to its orbit around the Sun. This tilt is what gives us our seasons. When the North Pole is tilted towards the Sun, it's summer in the Northern Hemisphere. Conversely, when it's tilted away, it's winter.

During the Vernal Equinox in the Northern Hemisphere, the Sun's center crosses the celestial equator moving northward. At this moment, day and night are approximately of equal length everywhere on Earth. This is why it's called an "equinox," which means "equal night" in Latin. After the Vernal Equinox, the days become longer and the nights become shorter in the Northern Hemisphere as the North Pole tilts towards the Sun. This trend continues until the Summer Solstice, when the North Pole is tilted furthest towards the Sun. In the Southern Hemisphere, the opposite is true. The Vernal Equinox marks the beginning of autumn, and the days become shorter while the nights become longer.

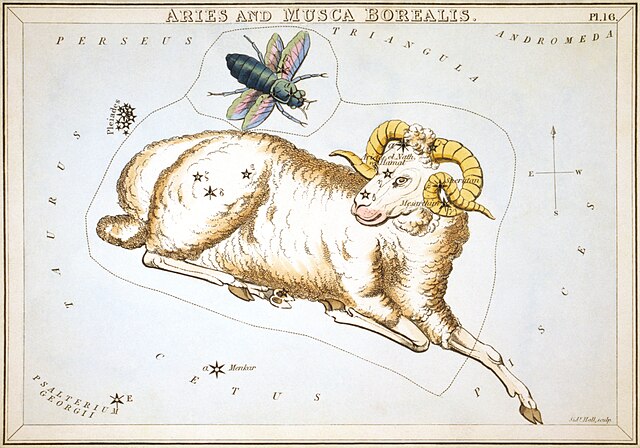

Astrological perspective

From an astrological perspective, the Vernal Equinox, also known as the Spring Equinox, marks a significant shift in energy and is associated with the zodiac sign of Aries. The Vernal Equinox is often associated with new beginnings, as it signifies the start of a new astrological year. It symbolizes the rebirth of nature after the dormant winter months. It's a time of growth, vitality, and renewed energy.

Aries and Musca Borealis as depicted in Urania's Mirror, a set of constellation cards published in London c. 1825 (source: Wikipedia)

Astrology divides the year into twelve signs, each associated with specific dates. The Vernal Equinox marks the transition from Pisces to Aries. The transition from Pisces (a Water sign) to Aries (a Fire sign) represents a shift from the dreamy, intuitive, and emotionally sensitive energy of Pisces to the bold, assertive, and dynamic energy of Aries. Aries is a Cardinal sign, which signifies initiation, leadership, and action. Aries is ruled by Mars, the planet of action, energy, and assertiveness. This sign is known for its willingness to take risks, pursue goals, and assert itself in various areas of life. Aries is often associated with individuality and independence. People born under this sign are thought to be self-driven, adventurous, and unafraid to blaze their own trail. Cardinal signs (Aries, Cancer, Libra, and Capricorn) mark the beginning of seasons, and Aries heralds the beginning of spring in the Northern Hemisphere.

Various gods and goddesses associated with the Spring Equinox

Here is a list of various gods and godesses associated with the Spring Equinox from cultures and belief systems around the world:

-

Adonis (Greek Mythology)

Adonis is a figure in Greek mythology associated with beauty, desire, and vegetation. His death and rebirth are linked to the changing seasons, with his return symbolizing the arrival of spring.

-

Astarte (Phoenician and Canaanite Mythology)

Astarte is an ancient goddess associated with fertility, love, and war. Celebrated in various ancient cultures, her worship often involved rituals tied to the changing seasons, including the arrival of spring.

-

Attis (Phrygian Mythology)

Attis is a Phrygian god associated with vegetation, life, and death. His mythology involves a resurrection theme, making him a symbol of renewal and the spring season.

-

Cernunnos (Celtic Mythology)

Cernunnos is a Celtic god associated with fertility, nature, and the wilderness. While not specifically tied to the Spring Equinox, his themes align with the rejuvenation of nature during spring.

-

Demeter (Greek Mythology)

Demeter, the Greek goddess of agriculture, is often honored during the Spring Equinox. Her sorrow over the loss of her daughter, Persephone, results in the barrenness of winter, and her joy at Persephone's return brings about the rebirth of spring and the growth of crops.

-

Ea (Sumerian Mythology)

Ea, also known as Enki, is a Sumerian god associated with wisdom, water, and fertility. While not specifically linked to the Spring Equinox, his role in agricultural aspects aligns with themes of growth and renewal.

-

Flora (Roman Mythology)

Flora, the Roman goddess of flowers and spring, is celebrated during the season when plants begin to bloom. The festival of Floralia, dedicated to Flora, is associated with the renewal of life and fertility.

-

Freya (Norse Mythology)

Freya, the Norse goddess of love, beauty, and fertility, is associated with the spring season. She is considered a patroness of fertility, and her presence is linked to the blossoming of nature.

-

Green Man (Pagan and Folklore Traditions)

The Green Man is a symbol found in various cultures and represents the spirit of the forest and nature's vitality. In modern pagan and folklore traditions, the Green Man is often celebrated during the spring.

-

Hathor (Egyptian Mythology)

Hathor, the Egyptian goddess associated with joy, love, and motherhood, is sometimes linked to the celebration of spring. Her festivities were characterized by music, dance, and expressions of joy, symbolizing the rejuvenation of life.

-

Idun (Norse Mythology)

Idun is a Norse goddess associated with youth and rejuvenation. Her role in providing the gods with magical apples that keep them eternally young aligns with themes of renewal and vitality, making her a symbol of spring.

-

Inanna (Sumerian)

Inanna is the Sumerian counterpart to Ishtar and shares similar attributes. She is a goddess of love, fertility, and war. Inanna is also known for her descent into the Underworld, a journey that mirrors Ishtar's. During her time in the Underworld, the earth languishes, but her return brings about the revitalization of nature.

-

Ishtar (Akkadian/Babylonian)

Ishtar is a prominent goddess in Babylonian and Akkadian mythology. She is associated with love, beauty, fertility, and war. Ishtar's most famous myth involves her descent into the Underworld, where she seeks to rescue her lover Tammuz. During her absence, the earth becomes barren, and life withers. Ishtar's return is celebrated with joy, symbolizing the renewal of life and fertility.

-

Jarilo (Slavic Mythology)

Jarilo is a Slavic god of fertility, vegetation, and springtime. He is often associated with the rebirth of nature and the agricultural cycle. The festival of Jare Gody celebrates Jarilo and typically takes place in the spring.

-

Mithras (Roman-Persian Mystery Religion)

Mithras, a god in the Roman-Persian mystery religion of Mithraism, is often associated with the sun and was worshipped during the Spring Equinox. His worship involved rituals linked to the changing seasons.

-

Osiris (Egyptian Mythology)

Osiris, the Egyptian god of life, death, and fertility, is often associated with agricultural cycles. His mythology includes themes of resurrection and rebirth, connecting him to the idea of spring renewal.

-

Ostara (Germanic Mythology)

Ostara, also known as Eostre, is a Germanic goddess associated with the spring equinox. She is considered a fertility goddess, and her name is thought to be the origin of the word "Easter." Traditionally, rabbits and eggs are associated with her, symbolizing fertility and new life.

-

Pan (Greek Mythology)

Pan is a Greek god associated with nature, shepherds, and rustic music. While not directly tied to the equinox, Pan's connection to the natural world aligns with the themes of spring.

-

Persephone (Greek Mythology)

Persephone, the daughter of Demeter, is a central figure in Greek mythology. Her story, involving her abduction to the Underworld and her return to the surface, is associated with the changing seasons. Her return marks the beginning of spring and the blossoming of nature.

-

Vesna (Slavic Mythology)

Vesna is a Slavic goddess associated with spring, warmth, and youth. Her name is derived from the Slavic word for "spring." She is celebrated for bringing the renewal of life and nature.

Various celebrations and traditions associated with the Spring Equinox

Here is a list of various celebrations and traditions associated with the Spring Equinox from cultures around the world:

-

Akitu (Ancient Babylon)

Akitu is the name of the Babylonian New Year's festival celebrated in ancient Mesopotamia, particularly in the city of Babylon.

-

Chunfen (China)

In Chinese culture, the Vernal Equinox is known as Chunfen, which translates to "Spring Equinox." It's considered one of the 24 solar terms in the traditional Chinese calendar. People observe this day as a marker of the transition from winter to spring.

-

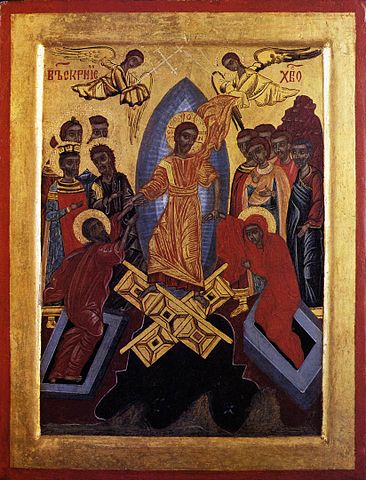

Easter (Christian community)

Easter, a Christian holiday, is tied to the Vernal Equinox. It celebrates the resurrection of Jesus Christ and the victory of life over death. The date of Easter is determined by the ecclesiastical approximation of the Vernal Equinox.

-

Higan (Japan)

In Japan, the Vernal Equinox is a time of reflection and a period of paying respects to deceased ancestors. Families visit graves, clean the burial sites, and offer flowers and food as a sign of respect.

-

Holi (Hindu community, India and worldwide)

Holi, also known as the Festival of Colors, is celebrated in India and other parts of South Asia around the time of the Vernal Equinox. It's a vibrant festival where people play with colored powders, dance, sing, and celebrate the arrival of spring.

-

Maya Equinox Celebrations (ancient Mayan culture, Mexico)

In ancient Maya culture, the Vernal Equinox was a significant astronomical event. At the temple of Kukulcan at Chichen Itza, a shadow play occurs on the equinoxes, creating the illusion of a serpent slithering down the temple's staircase.

-

Nowruz (Central Asia)

Nowruz, which means "New Day" in Persian, is a major celebration in Iran, among Persian-speaking communities, and various Central Asian communities including Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Kazakhs. It marks the beginning of the Iranian calendar year and coincides with the Vernal Equinox. It involves a wide range of traditions, including spring cleaning, family gatherings, festive meals, and the setting up of a "Haft-Sin" table with seven symbolic items.

-

Pagan and Neopagan Celebrations (Various)

In modern pagan and neopagan traditions, the Vernal Equinox is celebrated as a time of renewal, balance, and growth. It's often associated with rituals, ceremonies, and gatherings to honor nature, fertility, and the changing of the seasons.

-

Shunbun no Hi (Japanese community)

Shunbun no Hi, also known as the Spring (Vernal) Equinox Day, is a public holiday in Japan observed around the Spring Equinox. The holiday is also special to farmers and agriculturalists as a day to pray for good luck and fortune for the crops they may grow in the upcoming season.

-

Tekufat Nisan (Jewish community)

"Tekufat Nisan" refers to the vernal equinox in the Jewish calendar, specifically during the month of Nisan. The vernal equinox marks the beginning of spring, and Tekufat Nisan is significant in determining the timing of certain religious observances in Judaism.

Akitu

(Ancient Babylon)

Akitu or Akitum (Sumerian: 𒀉𒆠𒋾, Akkadian: 𒀉𒆠𒌈, lit. 'festival') is the name of the Babylonian New Year's festival celebrated around the first new moon after the spring (vernal) equinox, in ancient Mesopotamia, particularly in the city of Babylon. The festival had religious and cultural significance and was dedicated to the chief god Marduk. It's name comes from the word the Sumerians used for barley. The Akitu festival was one of the most important and widely observed celebrations in the Babylonian calendar. It played a crucial role in Babylonian religious and civic life, reflecting the ancient Mesopotamian worldview and the interconnectedness of the divine, natural, and human realms.

Royal procession passing through the Ishtar Gate on New Year's Day in ancient Babylon. Illustration by Peter Jackson, British (1922–2003)

Akitu was a multi-day festival that typically lasted for 11 days, coinciding with the vernal equinox, around late March or early April. It marked the beginning of the agricultural year and symbolized the renewal of life. The festival was dedicated to the god Marduk, the patron deity of Babylon and the chief god of the Babylonian pantheon. Akitu served as an opportunity for the people to reaffirm their loyalty and devotion to Marduk and to seek his blessings for a prosperous and fertile year ahead. Akitu involved elaborate ceremonial processions through the city streets. The statues of the gods, particularly Marduk, were paraded through the Ishtar Gate and taken to the Akitu House, a sacred building within the temple complex. One of the central activities during Akitu was the recitation of the Enuma Elish, the Babylonian creation epic. This mythological text narrates the story of Marduk's rise to supremacy among the gods and the creation of the world. Akitu included various rituals symbolizing purification, renewal, and the victory of order over chaos. During the Akitu, statues of the gods were paraded through the city streets, and rites were enacted to symbolize their victory over the forces of chaos. These rituals aimed to cleanse the city and its inhabitants from any negative influences, ensuring a fresh start for the new year. Offerings of food, drink, and other gifts were presented to the gods during Akitu. The festival also involved feasting and communal celebrations, with people coming together to share meals and enjoy various festivities.

A notable feature of the Akitu festival was a symbolic battle reenactment between Marduk and the forces of chaos, representing the victory of order and civilization. This theatrical performance symbolized the triumph of the god over the primordial forces of chaos. Akitu also had political significance, as the festival included the ritual "Taking of the Hand of Marduk," where the king, as the representative of Marduk on Earth, was symbolically married to the god. This ritual emphasized the divine legitimacy of the ruler and reinforced the bond between the divine and earthly realms.

Akitu was seen as a reenactment of the cosmic order and creation. The rituals and ceremonies were believed to influence the balance of cosmic forces and ensure a harmonious and prosperous year. Akitu was not only a religious event but also a time for social and cultural activities. It fostered a sense of community and unity among the people of Babylon, strengthening the bonds of the city-state.

Chunfen

(China)

Chunfen (春分), or the Spring Equinox, is one of the 24 solar terms in the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar, which is based on the position of the sun in the ecliptic. It typically occurs around March 20th or 21st in the Northern Hemisphere. "Chun" means spring, and "fen" means equinox. So, Chunfen literally translates to "Spring Equinox". Chunfen marks the point in time when the sun crosses the celestial equator, resulting in approximately equal lengths of day and night. It also represents a balance between yin and yang forces in nature, where yin (the passive, dark, and cold) and yang (the active, bright, and warm) are in equilibrium.

A Chinese family preparing dumplings, a popular food traditionally served on New Year’s Eve. (source: China Cultural Centre)

The annual CCTV New Year's Eva Gala show is transmitted on TV in China. (source: China Cultural Centre)

After Chunfen, days in the Northern Hemisphere become longer than nights as it progresses towards summer. It symbolizes the awakening of nature, with temperatures rising and the environment becoming more conducive to growth and life. It also signifies the time for farmers to start preparing for spring planting, as the weather becomes more favorable for agricultural activities. People may plant seeds or start preparing their gardens for the upcoming growing season.

Similar to the tradition in many cultures, Chunfen is a time for thorough cleaning of homes and surroundings. People believe that cleaning during this period helps remove any lingering negative energy from the winter and welcomes the fresh energy of spring. Chunfen is close to the Qingming Festival, also known as Tomb-Sweeping Day, which usually follows shortly after. During Chunfen, families may start preparations for Qingming, such as cleaning and maintaining ancestral graves.

Chunfen, like the other 23 solar terms, reflects the ancient Chinese understanding of the cyclical patterns of nature, allowing for practical applications in agriculture, traditional medicine, and cultural practices. For example, in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), Chunfen is believed to be a time when the body is more susceptible to the influences of the environment. People may adjust their diets and activities to align with the changing energy patterns.

Easter

(Christian community)

Easter is a Christian holiday that celebrates the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead, as described in the New Testament of the Bible. It is considered the most important and central event in Christianity. Easter holds significant theological and spiritual importance for Christians worldwide, and the celebrations can vary across denominations and cultural practices. The holiday is a time of joy, hope, and renewal for believers, marking the culmination of the Christian liturgical calendar.

Easter commemorates the resurrection of Jesus Christ on the third day after his crucifixion, as described in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John in the Bible. According to Christian belief, Jesus' resurrection is a symbol of victory over sin and death. The date of Easter varies each year and is determined based on the ecclesiastical approximation of the March equinox and the phases of the moon. It generally falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the vernal equinox, between March 22 and April 25. Easter is preceded by the season of Lent, a 40-day period of fasting, repentance, and prayer that symbolizes the 40 days Jesus spent in the wilderness. Lent begins on Ash Wednesday and concludes on Holy Saturday. The week leading up to Easter is known as Holy Week. It starts with Palm Sunday, commemorating Jesus' triumphant entry into Jerusalem, and includes Maundy Thursday (commemorating the Last Supper), Good Friday (commemorating the crucifixion), and Holy Saturday.

Many Christian denominations hold a special service called the Easter Vigil on Holy Saturday night. This service often includes the lighting of the Paschal candle, the proclamation of the resurrection, and the celebration of baptisms and confirmations. Easter Sunday is the central day of celebration. Churches hold sunrise services, and many Christians attend special church services to celebrate the resurrection. The atmosphere is one of joy and triumph.

The tradition of decorating and exchanging Easter eggs has both religious and pagan roots, which will be discussed later. Eggs are a symbol of new life and resurrection. In many cultures, people dye and decorate eggs, and egg hunts are organized for children.

Easter eggs, a symbol of the empty tomb, are a popular cultural symbol of Easter. (source: Wikipedia)

The Easter Bunny is a secular symbol of Easter, especially in Western cultures. It is a folklore figure who brings Easter eggs to children. The origin of the Easter Bunny is traced back to German folklore and has become a popular part of the secular celebration of the holiday.

Easter eggs, a symbol of the empty tomb, are a popular cultural symbol of Easter. (source: Wikipedia)

Different cultures have specific foods associated with Easter. In many places, a festive meal is shared with family and friends. Traditional foods vary, but lamb is a common choice due to its association with sacrifice in Christianity.

Various Christian denominations may have specific liturgical practices and traditions associated with Easter. For example, Eastern Orthodox Christians often celebrate Easter on a different date than Western Christians, and their traditions may differ.

Origin

The origins of Easter are multifaceted and include a mix of religious, cultural, and pagan influences. The celebration has evolved over centuries, with various customs and traditions becoming intertwined.

The roots of Easter can be traced back to ancient Babylon (festival called Akitu), to ancient pagan celebrations of spring, fertility, and renewal. Many cultures celebrated the vernal equinox as a time of new life and the end of winter. The name "Easter" may derive goddess from Eostre (Akkadian Ishtar, Sumerian Inanna). Eostre, also known as Ostara, was a goddess associated with the dawn, fertility, and the awakening of nature. While historical evidence of this goddess is limited, her name is believed to have influenced the naming of the Christian festival. Some historical references mention Eostre as a localized Germanic goddess.

The timing of Easter is linked to the vernal equinox. The choice of spring for the celebration of Jesus' resurrection holds symbolic significance. Just as nature undergoes a renewal during spring, Christians view the resurrection as a symbol of spiritual rebirth, renewal, and the triumph of life over death. Early Christians sought to align the celebration of Jesus' resurrection with the timing of existing spring festivals, making it more appealing to potential converts. The First Council of Nicaea, convened by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in 325 AD, played a significant role in establishing the date for Easter. The council determined that Easter should be observed on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the vernal equinox.

As Christianity spread across different regions, Easter assimilated various cultural traditions and practices. Different communities developed unique customs associated with the holiday. For example, the tradition of Easter eggs has ancient origins in various cultures. Eggs symbolize fertility and new life. Christians adapted the symbolism of eggs to represent the empty tomb from which Jesus emerged during his resurrection. The practice of decorating eggs became widespread. The Easter Bunny, a popular secular symbol, has its origins in German folklore. The hare, known for its fertility, became associated with springtime, and the tradition of an egg-laying bunny was brought to America by German immigrants in the 1700s.

In summary, Easter has complex and intertwined origins that encompass both Christian and pre-Christian traditions. Over time, it has become a diverse and widely celebrated holiday with a rich complexity of customs and practices.

Higan

(Japan)

Higan, also known as Higan-e, is a traditional Japanese Buddhist observance that takes place during the spring and autumn equinoxes. The word "Higan" means "the other shore" in Japanese and is used to signify the crossing over from the world of delusion to enlightenment. The observance typically lasts for about a week, with three days leading up to the equinox, the day of the equinox itself, and three days following the equinox. Higan is specifically associated with the spring and autumn equinoxes, which occur around March 20-21 and September 22-23, respectively. During these times, day and night are of nearly equal length, symbolizing balance and harmony. The day of the spring equinox is a national holiday in Japan known as Shunbun no Hi. The autumn equinox is also a public holiday called Shubun no Hi. Many people take advantage of the extended break to observe Higan rituals, spend time with family, and connect with Buddhist teachings.

Higan is a time for Buddhists in Japan to reflect on the transient nature of life, practice mindfulness, and express gratitude for the blessings of the present moment. It is believed that during Higan, the spirits of the deceased are thought to be closer to the living, and people often pay their respects to their ancestors. Buddhist temples hold special services during Higan. These services include sutra recitations, meditation, and dharma talks that focus on themes related to enlightenment, impermanence, and the path to liberation. Higan encourages individuals to live mindfully and in accordance with Buddhist principles. Practicing virtues such as generosity, kindness, and compassion is emphasized during this time. It is a period for self-reflection and a recommitment to the Buddhist path.

One of the common practices during Higan is visiting family gravesites. People clean and maintain the graves, offer flowers, burn incense, and make offerings of food. This ritual is a way to express filial piety, remember ancestors, and wish for their well-being in the afterlife.

Higan is also associated with the preparation and consumption of special foods known as "ohagi" during the spring observance and "botamochi" during the autumn observance. These are rice cakes covered with sweet red bean paste or soybean flour. The round shape of the sweets represents the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

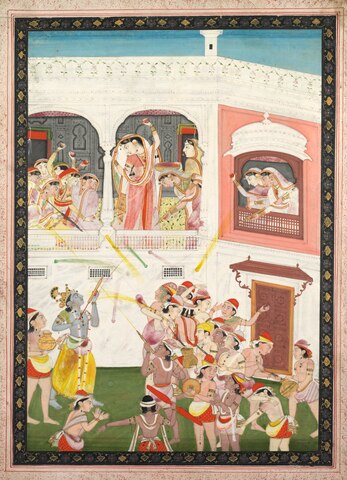

Holi

(India, Hindu community)

Holi, also known as the Festival of Colors, is one of the most vibrant and joyous festivals celebrated in India. It marks the arrival of spring, the triumph of good over evil, and a time of revelry, camaraderie, and the splashing of colorful powders. Holi usually takes place in March, with the date determined by the Hindu lunar calendar. The festival has various cultural and religious significances. It is associated with the legend of Lord Krishna and Radha, where Krishna is said to have playfully colored Radha's face. The festival also marks the end of winter and the arrival of spring, symbolizing renewal and the triumph of good over evil.

Radha and Hindu God Krishna Celebrating the Festival Holi (Bilaspur School, Pahari Hills, India, 19th century)

The festivities often begin with Holika Dahan, also known as Choti Holi, on the night before the main day of Holi. Bonfires are lit to commemorate the victory of good over evil and the burning of the demoness Holika. People gather around the bonfire, perform rituals, and sing and dance.

The main day of Holi, known as Rangwali Holi, is celebrated with the iconic throwing of colors. People of all ages take to the streets, parks, and open spaces, armed with colored powders (gulal) and water balloons. The air is filled with laughter, music, and the joyous shouts of "Holi Hai!" (It's Holi!). Participants joyfully smear each other with vibrant colors, turning the surroundings into a kaleidoscope of hues. Water balloons and water guns are also used to playfully drench friends and strangers alike. The emphasis is on fun, unity, and breaking down social barriers. Traditional Holi songs, known as "Holi ke Geet" or "Holi ke Rasiya," are played during the celebrations. People dance to the energetic beats, creating a lively and festive atmosphere. Bhang (a traditional Indian cannabis-infused beverage) is sometimes consumed during Holi, adding to the merriment. Holi is also a time for feasting on special foods and sweets. Gujiya, a sweet dumpling filled with khoya (reduced milk), and other traditional snacks are prepared and shared among family and friends. Thandai, a cold milk-based drink infused with spices and nuts, is a popular beverage during Holi.

The second day of Holi is often called Dhulandi or Dhuleti, emphasizing the playing with colors. It is a day when people continue to indulge in color play, expressing their joy and enthusiasm.

Holi is a time of uninhibited joy, where the boundaries between people dissolve in a burst of colors. It is celebrated with exuberance not only in India but also by communities around the world, making it one of the most widely recognized and cherished Indian festivals.

Maya Equinox Celebrations

(Mexico, ancient Mayan culture)

The Maya civilization, known for its advanced understanding of astronomy and complex calendrical systems, placed significant importance on celestial events, including equinoxes. These astronomical events held cultural and ritual significance for the ancient Maya. While there is limited direct evidence, scholars have pieced together insights into Maya equinox celebrations through archaeological and astronomical research.

The Maya were skilled astronomers and architects, and many of their ceremonial structures, such as temples and ball courts, exhibit alignments with celestial events, including the equinoxes. Scholars have identified instances where certain Maya structures align with the rising or setting sun during the equinoxes, suggesting intentional planning and design. One of the most famous examples of Maya architecture aligned with the equinoxes is the pyramid known as El Castillo at the archaeological site of Chichen Itza in Mexico. On the days surrounding the spring and fall equinoxes, a fascinating light-and-shadow phenomenon occurs on the staircase of El Castillo. The sunlight creates the illusion of a serpent descending the steps, symbolizing the feathered serpent deity Kukulkan.

The descent of the serpent effect observed at Temple of Kukulcán during the spring equinox. (El Castillo, Chichen Itza, 2009)

While the exact details of Maya equinox celebrations remain elusive, it is likely that these celestial events held ritual significance. Maya inscriptions and codices, along with depictions on pottery and murals, suggest that celestial events were intertwined with religious and ceremonial practices.

They played a ceremonial ball game with religious significance, and the ball courts often exhibit astronomical alignments. Some scholars propose that the equinoxes may have been associated with specific rituals or ceremonies related to the ball game. In some Maya sites, natural features like cenotes (natural sinkholes) were considered sacred. Rituals and ceremonies involving water, purification, and offerings may have been part of equinox celebrations. While the ancient Maya civilization declined centuries ago, some indigenous Maya communities continue to celebrate traditional rituals and ceremonies that may have roots in ancient practices. These modern-day celebrations often involve a blend of traditional and syncretic elements.

Ongoing archaeological and anthropological research continues to unveil new insights into Maya equinox celebrations. Advances in technology, including LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), have allowed researchers to uncover hidden structures and further understand the extent of Maya astronomical knowledge. While much is still to be discovered, the Maya celebrations serve as a testament to the intricate relationship between the ancient civilization and the cosmos, reflecting a profound understanding of astronomy, architecture, and ritual practices.

Nowruz

(Central Asia)

Nowruz, also spelled as Norooz or Nawruz, is the Persian New Year and the traditional celebration of the arrival of spring. It has been celebrated for over 3,000 years and holds great cultural and historical significance in various communities, particularly in Iran and Central Asia. Nowruz usually takes place on or around March 20th or 21st, marking the vernal equinox.

Nowruz has roots in ancient Zoroastrian traditions and is deeply ingrained in the cultural heritage of the Iranian people. Over time, it has become a secular celebration observed by diverse communities in the Middle East, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and among diaspora populations around the world. Nowruz translates to "New Day" and symbolizes the triumph of light over darkness, good over evil, and the renewal of nature. It marks the beginning of the Iranian solar year and the first day of the month of Farvardin in the Iranian calendar.

One of the central elements of Nowruz is the Haft-Seen table, a festive spread that includes seven symbolic items, all starting with the Persian letter "S" (س). These items typically include Sabzeh (sprouted wheat or barley representing rebirth), Samanu (sweet pudding symbolizing power and strength), Senjed (dried oleaster fruit symbolizing love), Seer (garlic symbolizing medicine and health), Seeb (apples symbolizing beauty and good health), Somāq (sumac berries symbolizing the sunrise and patience), and Serkeh (vinegar symbolizing aging and patience).

In the weeks leading up to Nowruz, families engage in a thorough spring cleaning of their homes. This tradition, known as "Khane Tekani" symbolizes the removal of the old and the preparation for a fresh start in the new year.

The festivities kick off with Chaharshanbe Suri, a pre-Nowruz event held on the eve of the last Wednesday of the year. People light bonfires and jump over them, symbolically casting away their troubles and sorrows while seeking the return of the warmth and light of the fire. Nowruz is a time for family gatherings and visiting friends and relatives. People exchange gifts and well-wishes for the new year. Elders give money or gifts to younger members of the family, a tradition known as "Eidi." On the day of Nowruz, families come together for a festive meal, and many communities attend public events and celebrations. It is customary to wear new clothes, and there is an emphasis on positivity, joy, and optimism for the year ahead.

The Nowruz celebrations typically extend for 13 days, culminating in Sizdah Bedar, a day for outdoor activities and picnics. On this day, people spend time in nature, especially in parks and green spaces, to ward off bad luck associated with the number 13.

Nowruz is recognized as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO, highlighting its global significance and the shared cultural practices associated with the celebration. It serves as a symbol of unity, renewal, and the rich cultural heritage of the diverse communities that observe it.

Pagan and Neopagan Celebrations

(Pagan and neopagan community)

Pagan and Neopagan communities celebrate the Spring Equinox, also known as Ostara, as a time of balance, renewal, and the awakening of the earth. These celebrations draw inspiration from various pagan traditions, including Wicca and other modern spiritual practices. While specific rituals and customs can vary among different groups.

In Wicca and many Neopagan traditions, the Spring Equinox is celebrated as one of the eight Sabbats on the Wheel of the Year. Ostara, named after the Germanic goddess associated with spring and fertility, is a time to honor the balance between light and dark, the returning warmth, and the reawakening of the natural world. Eggs and hares are prominent symbols during Ostara celebrations. Eggs represent fertility, new life, and potential, while hares are associated with the goddess Ostara and the moon. Many Pagan rituals incorporate the coloring and decorating of eggs as a symbol of creative potential and the rebirth of nature. Altars are set up with seasonal decorations that symbolize the themes of Ostara. Common items include fresh flowers, especially those in vibrant spring colors, seeds, and symbols of fertility. Some practitioners also incorporate representations of animals associated with spring, such as chicks or lambs.

Spring Equinox rituals often focus on the themes of balance and harmony. This is a time to reflect on the equilibrium between day and night, light and dark. Rituals may include activities that bring balance to one's life, such as meditation, visualization, or symbolic gestures like walking a labyrinth. Ostara is a celebration of the fertility of the land, and many Pagan and Neopagan practitioners engage in planting activities during this time. This could involve planting seeds or tending to a garden as a way of participating in the Earth's renewal.

Shared meals and feasts are common during Ostara celebrations. Traditional foods may include fresh fruits, vegetables, eggs, and other seasonal offerings. It is a time for community and sharing, fostering a sense of connection with others. Some Pagan groups celebrate Ostara with outdoor rituals, often involving bonfires. These fires symbolize the increasing power of the sun and serve as a focal point for communal gatherings. Dancing, singing, and drumming are common activities around the bonfire. Celebrations often include crafting activities related to the season. This could involve making wreaths, painting eggs, creating art that reflects the themes of renewal, or engaging in other hands-on projects.

Practitioners may invoke specific deities associated with spring and fertility during Ostara rituals. In addition to Ostara, other deities from various pantheons, such as Persephone, Demeter, or Eostre, may be honored. Some traditions, particularly those influenced by Druidic or Celtic practices, may incorporate elements of their respective cultural and historical celebrations into Ostara rituals. This can include references to specific deities, folklore, and traditional symbols.

It's important to note that Pagan and Neopagan celebrations are diverse, and practices can vary widely among different traditions and individual practitioners. The above description provides a general overview, and the specifics of Ostara celebrations may differ based on the beliefs and preferences of those involved.

Shunbun no Hi

(Japanese community)

Shunbun no Hi (春分の日), also known as Spring (Vernal) Equinox Day, is a public holiday celebrated in Japan to mark the spring equinox. It typically falls around March 20th or 21st each year. It is part of a seven-day period of festival called Haru no Higan. The celebration of Shunbun no Hi is very significant from ancient days to this day.

Historically, Shunbun no Hi has its roots in ancient Japanese agricultural rituals and beliefs. It's tied to the changing seasons and the transition from winter to spring. In ancient times, the equinoxes were important markers for agricultural activities. The vernal equinox signaled the beginning of the planting season, so rituals and ceremonies were performed to pray for a successful harvest and to honor nature and the spirits. Shunbun no Hi is also associated with paying respects to ancestors. Families often visit ancestral graves during this time, cleaning and decorating them with flowers and offerings.

Today, Shunbun no Hi is celebrated as a public holiday in Japan, giving people time off to relax and spend time with family and friends. Many people will return to their homes they originally come from to spend the day with their families. Many people take the opportunity to enjoy outdoor activities such as picnics, cherry blossom viewing (Hanami - jap. 花見; trans. "flower viewing")), and nature walks, as the weather begins to warm up and flowers start to bloom. It's also a time for reflection and renewal, with some individuals taking the opportunity to engage in spiritual practices or visit temples and shrines.

Since 1948, Shunbun no Hi has been designated as a national holiday in Japan. This means that most businesses, schools, and government offices are closed, allowing people to observe the holiday.

Tekufat Nisan

(Jewish community)

Tekufat Nisan, or Nisan Equinox, is an astronomical and calendrical event associated with the Jewish calendar. It marks the vernal equinox, which usually occurs around March 20th or 21st in the Gregorian calendar. Nisan is the first month of the Jewish ecclesiastical year and the seventh month of the civil year. The equinox plays a significant role in determining the timing of certain Jewish holidays, particularly Passover (Pesach).

Tekufat Nisan is linked to the vernal equinox, the moment when the sun crosses the celestial equator. In the Jewish calendar, this equinox is used to determine the beginning of Nisan. The determination of the new moon and the equinox helps establish the timing of Rosh Chodesh (the beginning of the new month) and, consequently, the start of Nisan. Nisan is a significant month in the Jewish calendar as it marks the liberation of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt during the Exodus.

Replica of a mosaic from Hamat Tiberias synagogue in Ashkelon Academic College, Ashkelon, Israel. Symbol for springtime (תקופת ניסן) is in upper left corner: the lady holds in her right hand a beautiful dish filled with pastry, her hair is tied up with strings, while her curls are falling nicely on her neck, new buds are appearing at her left and her eyes are gazing but also attending (source: Wikipedia)

The holiday of Passover (Pesach), one of the most important Jewish festivals. It begins on the 15th day of Nisan and lasts for seven or eight days, depending on Jewish tradition. The equinox and the subsequent new moon help determine when Nisan begins, aligning with the commandment in the Torah to observe Passover at the appointed time.

Birkat Hachama is a Jewish tradition also associated with Tekufat Nisan. It involves reciting a special blessing, expressing gratitude for the sun's position at the time of the vernal equinox, which occurs approximately once every 28 years. This ceremony emphasizes the cyclical nature of time and the sun's role in the calendar.

The determination of the equinox and Tekufat Nisan reflects the intricate interplay between astronomy, religion, and culture in Jewish tradition. It illustrates how the Jewish calendar incorporates both lunar and solar elements to regulate the timing of religious observances. And while Tekufat Nisan itself is not a holiday, its occurrence is acknowledged, and some communities may engage in special prayers or reflections.