The Alphabet - Origins and Evolution

The written alphabet stands as one of humanity’s greatest intellectual triumphs, forming the cornerstone of communication, literature, and recorded knowledge. Early traces of alphabetic systems emerge as far back as 2400 B.C., with archaeological discoveries showcasing the slow transformation of symbols into organized scripts. Although the Egyptians are frequently acknowledged as pioneers, their hieroglyphic script remained primarily ceremonial - reserved for sacred carvings rather than daily use.

The Phoenicians: Pioneers of the Written Word

The Phoenicians, celebrated as master merchants and intrepid navigators of the ancient world, left an indelible mark on history through their revolutionary contributions to writing. Hailing from the coastal cities of the Levant - such as Byblos, Tyre, and Sidon - they established a vast trading empire that stretched across the Mediterranean and beyond. Their commercial prowess demanded an efficient method of recording transactions, contracts, and communications, which spurred one of their greatest legacies: the development of the alphabet.

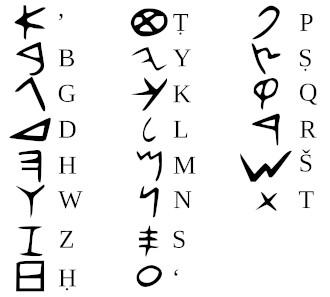

Building upon earlier Semitic scripts, the Phoenicians refined and simplified writing into a consonantal system of approximately 22 characters. Unlike the complex pictograms of Egyptian hieroglyphs or the cumbersome cuneiform of Mesopotamia, their alphabet was remarkably streamlined, allowing for quicker notation and broader accessibility. This innovation not only facilitated trade but also laid the foundation for future writing systems, including Greek, Latin, and ultimately, the alphabets used throughout the Western world.

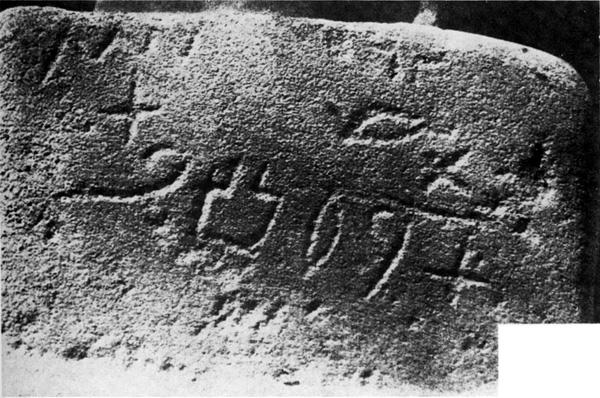

The Phoenician alphabet similar to that used on the Mesha Stele (source: commons.wikimedia.org)

Through their extensive maritime trade networks, the Phoenicians disseminated their script to distant shores, influencing cultures from Carthage to Iberia and beyond. Greek historians later credited them with introducing writing to the Hellenic world, where their alphabet was adapted to include vowels, further enhancing its versatility.

Beyond commerce, the Phoenician alphabet enabled the preservation of knowledge, the administration of empires, and the flourishing of literature. Their legacy endures in every letter we write today - a testament to their ingenuity as not just traders of goods, but as traders of letters that shaped human civilization.

The Greeks: Architects of the Alphabet

When the Phoenician alphabet arrived in Greece around the 8th century BCE, it sparked a linguistic revolution. The Greeks recognized the potential of this writing system but adapted it to suit their own language, making a crucial innovation: the introduction of vowel signs. By repurposing certain Phoenician consonants that had no equivalent in Greek, they created distinct symbols for alpha, epsilon, iota, omicron, and upsilon - sounds essential to their speech. This transformation made writing more precise and accessible, allowing for a clearer representation of spoken language.

Beyond functionality, the Greeks infused their script with artistic elegance. The rigid, angular forms of Phoenician letters were softened into graceful, symmetrical curves, reflecting the Hellenic appreciation for beauty and harmony. Over time, regional variations emerged, with the eastern Ionic script eventually becoming the standard classical Greek alphabet.

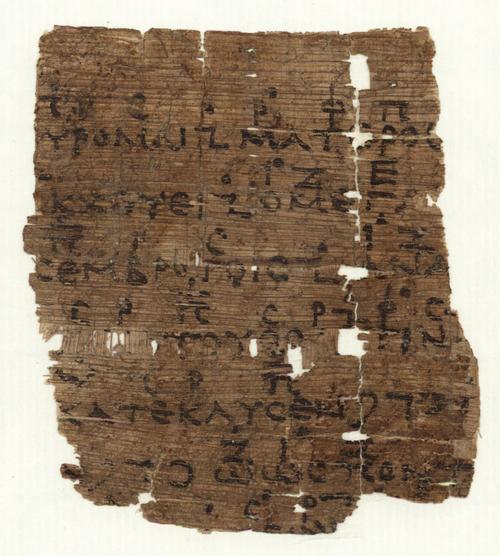

Musical fragment from the first stasimon of Orestes by Euripides (source: commons.wikimedia.org)

The Greek alphabet’s influence was immense. It spread to the Etruscans in Italy, who then passed it to the Romans. The Romans further refined it, developing the bold, geometric capitals that adorned their monuments and legal documents. These Roman capitals became the foundation of modern uppercase letters in Western alphabets.

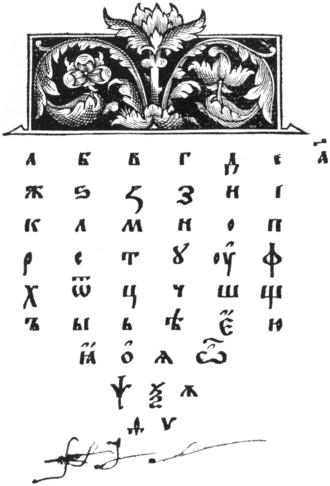

Meanwhile, the Byzantine Greeks preserved and evolved the script into the minuscule cursive that influenced Cyrillic and modern Greek writing. From philosophy to poetry, the Greek alphabet became the vessel for some of history’s greatest intellectual and literary achievements.

A page from Буквар (Bukvar/Reader), the first Old Slavonic textbook, printed by Ivan Fyodorov in 1574 in Lviv. (source: commons.wikimedia.org)

Thus, the Greeks did not merely adopt the alphabet - they perfected it, ensuring its endurance as one of humanity’s most transformative inventions. Their legacy lives on in every book, every street sign, and every word we read today.

From the Dark Ages to the Renaissance

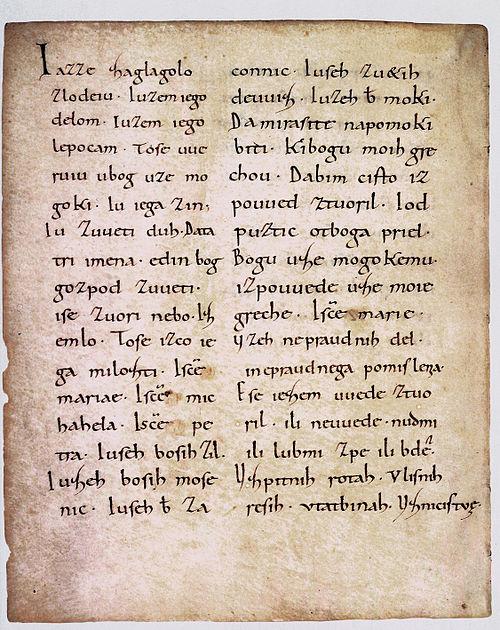

The fall of the Roman Empire plunged Europe into centuries of upheaval, yet the alphabet - like a resilient torch in the darkness - endured. As the centralized power of Rome crumbled, regional scribal traditions arose, each adapting the Latin script to local needs. In the scriptoria of medieval monasteries, Benedictine monks meticulously preserved classical knowledge, their quills shaping letters into the stately Carolingian minuscule - a clear, uniform script championed by Charlemagne’s scholars. This reform laid the groundwork for modern lowercase letters, marrying Roman capitals with more fluid, readable forms.

A page of the Freising manuscripts, showing 10th-century Slovene text written in Carolingian minuscule. Bavarian State Library, Munich. (source: commons.wikimedia.org)

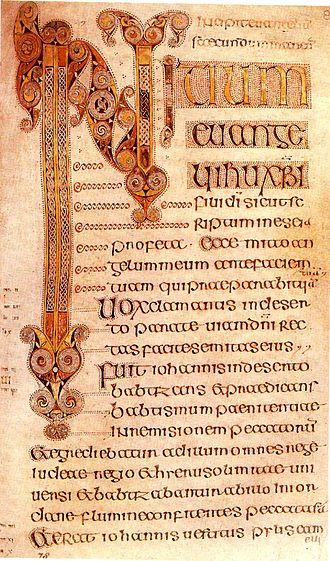

Meanwhile, the alphabet absorbed new influences at Europe’s edges. Norse runes left their mark in Anglo-Saxon England, where scribes blended them with Latin to write Old English, adding letters like thorn (þ) and wynn (ƿ). In Spain, Visigothic script flourished, while Irish monks developed the intricate, serpentine curves of Insular script, preserving sacred texts like the Book of Kells. Even as feudalism fragmented Europe, the alphabet remained a unifying thread, adapting to dialects and political shifts.

Decorated text from the Book of Durrow, beginning of the Gospel of Mark (source: commons.wikimedia.org)

By the 12th century, Gothic blackletter emerged - its dense, angular strokes mirroring the towering cathedrals of the age. Yet this ornate style, though majestic, proved impractical for the rising literate classes. The Renaissance’s revival of classical ideals brought a return to cleaner, humanist scripts inspired by Carolingian models. With the invention of movable type, Johannes Gutenberg’s 42-line Bible (1455) cemented the alphabet’s modern form, optimizing letter shapes for mass production.

By 1500, superfluous characters like þ and ƿ had faded, while “I” and “J” split into distinct letters, and “U” and “V” parted ways. The 26-letter system crystallized, a perfect vessel for the era’s explosion of literature, science, and exploration. From Shakespeare’s quill to Newton’s equations, this refined alphabet proved endlessly versatile - a testament to its medieval metamorphosis. Far from stagnating in the “Dark Ages,” it had evolved into humanity’s most enduring tool for capturing thought.

Where Letters Meet Mathematics

Far more than simple symbols, the letters of our alphabet form a sophisticated mathematical matrix - a coded system where language and numbers intertwine. This concept, stretching back to antiquity, reveals that writing has always been as much about calculation as communication.

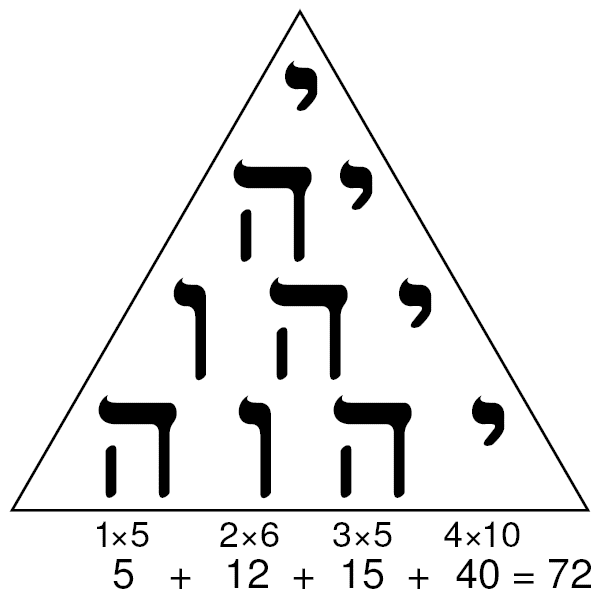

The ancient practice of gematria, used by Hebrew, Greek, and Babylonian scholars, assigned numerical values to letters, transforming words into equations. In Hebrew scripture, the sum of a word’s letters often carried mystical meaning - the famous example of chai (life) totaling 18 made it a sacred number in Judaism. The Greeks, inheriting this tradition, encoded philosophical ideas in their alphabet: Plato’s Academy reportedly inscribed "Let no one ignorant of geometry enter" over its door, hinting at the deep link between letters and mathematics.

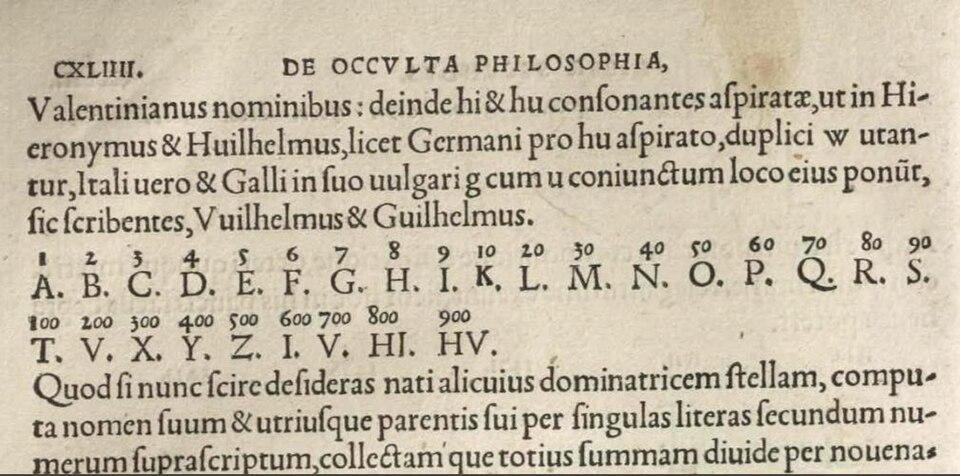

Medieval alchemists and Renaissance thinkers like Pythagoras believed letters held vibrational essences, their numerical values unlocking cosmic truths. The Roman alphabet, too, followed this logic - its letters doubled as numerals (I, V, X, L, C, D, M), allowing ancient scribes to record dates, sums, and prophecies in a single stroke. Even today, we unconsciously engage with this legacy when we use "A-list" or "Plan B," echoing letter hierarchies rooted in numerical order.

A tetractys of the letters of the Tetragrammaton adds up to 72 by gematria. (source: commons.wikimedia.org)

The Agrippa Cipher, pg. 143 of De Occulta Philosophia 1533 (source: commons.wikimedia.org)

Modern computing has resurrected this ancient fusion. Binary code, Unicode, and ASCII all reduce letters to numerical values - proof that the alphabet’s mathematical DNA persists in the digital age. From sacred geometry to cryptography, letters remain vessels of hidden structure, whispering that language was never just about speech, but about the silent, eternal language of numbers.

The Numeric Revolution

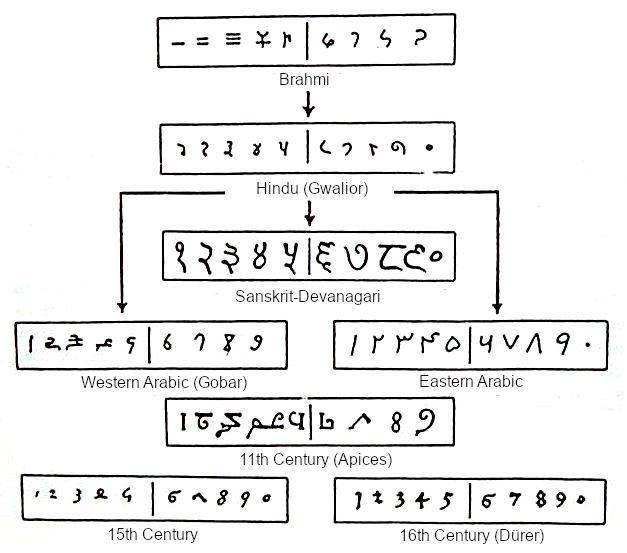

Though we refer to our modern digits as "Arabic numerals," their story begins much earlier in the intellectual crucible of ancient India. Around the 5th century CE, Indian mathematicians made a conceptual leap that would change human civilization forever - they formalized the number zero (sanskrit śūnya, meaning "void"), transforming it from a philosophical abstraction into a working mathematical tool.

This innovation did more than just fill a placeholder - it birthed the positional decimal system, where a digit's value depends on its place (units, tens, hundreds). Suddenly, complex calculations became streamlined, and mathematics leaped forward. The system's elegance was undeniable: where Roman numerals struggled with cumbersome notations (like MDCCCLXXVII for 1877), the new system could express any number with just ten symbols (0-9) through simple placement.

Arab scholars, encountering these numerals through trade and cultural exchange, recognized their power. By the 9th century, mathematicians like Al-Khwarizmi (whose name gives us the word "algorithm") were refining and promoting the system across the Islamic world. His seminal work On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals became the bridge that eventually carried these numerals to Europe.

Evolution of Indian numerals into Arabic numerals and their adoption in Europe (source: commons.wikimedia.org)

Resistance in the West was fierce - medieval European merchants clung to Roman numerals, and some authorities even banned the "infidel" symbols. But practicality won out. When Fibonacci introduced them in his 1202 Liber Abaci, demonstrating their superiority for commerce and accounting, the tide turned. By the Renaissance, the system had conquered Europe, enabling the scientific revolution.

Today, this global numeric language powers everything from supercomputers to supermarket receipts - all thanks to an idea born in India, nurtured by Arab scholars, and adopted by the world. The story of our numbers is a testament to how human ingenuity crosses borders, turning abstract concepts into the invisible foundation of modern life.

Alphabet's Cradle

The dominant narrative of the alphabet's birth along the Phoenician coast is now being challenged by groundbreaking archaeological discoveries that point to earlier, more diverse origins. Recent excavations at sites like Serabit el-Khadim in Egypt's Sinai Peninsula and ancient Canaanite settlements in Syria have unearthed proto-alphabetic inscriptions dating back to 1900-1500 BCE - centuries before Phoenician script emerged.

These enigmatic carvings, often found near turquoise mines and temples, reveal a fascinating hybrid system. Mine workers and Semitic slaves appear to have adapted Egyptian hieroglyphs into a simplified, consonantal writing method. The famous "Sinai Script" inscriptions show hieroglyphic symbols repurposed to represent sounds rather than concepts - a revolutionary cognitive leap. At Wadi el-Hol in Egypt, similar Semitic writings from the same period suggest this innovation may have traveled with migrant workers along trade routes.

Proto-Sinaitic inscription #346, the first published photograph of the script. (source: commons.wikimedia.org)

The implications are profound:

- Multicultural Innovation: Rather than being a purely Phoenician invention, the alphabet may have emerged from cultural intersections between Egyptians, Canaanites, and Semitic tribes

- Earlier Timeline: If verified, these findings would push the alphabet's origins back 500 years earlier than previously believed

- Sacred Context: Many early inscriptions appear in religious settings, hinting that writing may have served ritual purposes before becoming a tool of commerce

Biblical scholars note intriguing correlations with Exodus narratives describing early Hebrew writing. While the "Phoenician-first" theory remains dominant, these discoveries paint a richer picture of the ancient Near East as a laboratory of writing systems, where multiple cultures contributed to literacy's dawn. As excavations continue, we may need to rewrite the alphabet's origin story - not as a single invention, but as a collective human breakthrough forged across deserts and dynasties.

The Unbroken Chain of Letters

As we trace the alphabet's 4,000-year odyssey - from the wind-scoured cliffs of the Sinai to the glowing screens of the digital age - we witness nothing less than the evolution of human consciousness itself. What began as miners' scratches in Egyptian turquoise quarries has become the foundation of global civilization, mutating through countless hands: Phoenician merchants tallying cedar logs, Greek philosophers debating in the Agora, Roman bureaucrats recording edicts, medieval monks illuminating manuscripts, and Silicon Valley engineers designing Unicode.

This living system continues to transform before our eyes. Emoji evolve as modern pictograms, while texting abbreviations like "LOL" follow the same streamlining impulse that simplified cuneiform into alphabets. The recent addition of the Cherokee syllabary to Unicode proves the alphabet remains inclusive, absorbing new writing systems just as it once absorbed Greek vowels. Even AI-generated text, with its predictive algorithms, represents the latest chapter in our eternal quest to externalize thought.

A variety of emoji as they appear on Google's Noto Color Emoji set as of 2024. (source: commons.wikimedia.org)

Yet beneath these changes, the core miracle endures: twenty-six shapes can contain all human knowledge, from grocery lists to galactic equations. As we swipe keyboards today, we participate in history's most successful intellectual technology - one that has outlasted empires, survived the Dark Ages, and now conquers the digital frontier. The alphabet's story isn't just about writing; it's about humanity's stubborn refusal to let ideas disappear.

For deeper exploration:

- "The Alphabet Effect" by Robert K. Logan - Examines how alphabetic literacy shaped Western thought

- "Letter Perfect" by David Sacks - A lively biography of each letter's journey

- "The Writing Revolution" by Amalia E. Gnanadesikan - Traces scripts from cuneiform to Unicode

- "The Book" by Keith Houston - A visual history of writing technologies

In every text message, street sign, and subtitled film, the alphabet's legacy breathes - a testament to our shared human genius for turning marks into meaning.